1. Introduction

A History of the World in 100 Objects was a landmark series on BBC Radio 4 which told a narrative global history through the British Museum’s collection. The objects were also on display in the Museum during the period of the broadcast. These two components formed the core of the wider project - A History of the World – that the British Museum and BBC jointly conceived as a public service project in which the two organisations were equal partners. This has to be seen in the light of the formal status of the two institutions in the UK: the British Museum, a national Museum with grant-in-aid government funding, and the BBC, funded principally by an annual television licence fee charged to all United Kingdom households with a television, and a remit to provide a public service.

This paper looks at the scope of the A History of the World project, explaining how the partnership used each of the 3 media (on air, online and onsite) to strengthen engagement and further reach. For example, events around the country were used to develop interest and participation in the online project, while content contributed online was selected and made into broadcast content. Ideally, the consumer of and participant in A History of the World moved among the three facets of the project – the broadcasts (on air) , the gallery (on site), and the digital (online), each of which provided a different experience, complementing and amplifying each other, while contrasting in tone and texture. (In reality, many people will have experienced the project through only one or two media.) A high level of public awareness and interest was sustained precisely because of this orchestrated cross-media presence throughout the UK over the 10 months. Some indication of the reach of the project is contained in the figure of 18 million podcast downloads (worldwide) of the radio broadcasts in 2010, and initial evaluation suggesting that 1/3 of the UK population (20.6 million people) were aware of the BM/BBC partnership, with 24% of the UK population (14.8 million people) having listened to at least one episode.

2. A History of the World on air

The 15-minute programmes were narrated by Neil MacGregor, the Director of the British Museum, and broadcast in prime broadcast slots Monday to Friday in 3 parts across 2010.

| Part 1 | 18 January – 26 February 2010 | Object 1-30 |

| Part 2 | 17 May – 19 July 2010 | Object 31-70 |

| Part 3 | 13 September – 22 October 2010 | Object 71-100 |

For radio, the scale of the series alone was ambitious. Before A History of the World, the longest narrative history series was Professor David Reynolds’ America, Empire of Liberty which was broadcast in 90 15-minute episodes in 2008. It had a far more standard online offer and no related activity in other media beyond broadcasting (http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/america).

Radio is a medium that, superficially, could be seen as an unusual choice for a series which focuses on something as tangible as museum objects. However, according to Mark Damazer, controller of Radio 4 (2004-10), this was not a problem but an opportunity. By removing the visual, the programmes could give greater prominence to each object’s story. The medium of radio enabled each object to be used as prism through which to explore past worlds – and more could be conveyed on radio in 15 minutes than would ever have been possible on TV. The objects were described as far as it was necessary to tell that story, and conjure the object, and its significance into the listener’s mind.

Fig 1. Olduvai handaxe, A History of the World in 100 Objects, episode 3 http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/I3I8quLCR8exvdZeQPONrw

Fig 1. Olduvai handaxe, A History of the World in 100 Objects, episode 3 http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/I3I8quLCR8exvdZeQPONrw

A handaxe like this was the Swiss Army knife of the Stone Age - an essential piece of technology with multiple uses. The pointed end could of course be used as a drill, while the long blades on either side would cut trees or meat or scrape bark or skins. You can imagine using this to butcher an elephant, to cut the hide and remove the meat. (A History of the World in 100 Objects, episode 3 - Olduvai handaxe)http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/about/transcripts/episode3/

The costs of such a series on television would have been prohibitive given the range of locations needed. The programmes would inevitably have become a more generalised history, focused less on the object and more on the location of its origin. Radio offered both depth and focus. The use of the website to add the visual dimension gave listeners a chance to see and study each object, without detracting attention from the audio narrative that was being woven around each object.

Civilisation, a 13-part TV series broadcast by the BBC in 1969, was a landmark project to which A History of the World in 100 Objects has been compared, and is interesting to contrast. Presented by Kenneth Clark (later Sir Kenneth and Lord Clark), it covered Western European culture from the fall of the Roman Empire up to the industrial age of the 19th century. Unlike A History of the World in 100 Objects, it did not take artefacts as the subject matter or starting point for the programmes; rather these were treated as illustrations of the various phases of cultural history. Nevertheless, to give an idea of how immense the project was, objects in 118 museums and eighteen libraries were filmed, and 117 locations were used across eleven countries, during the three years of filming (1966-69) (Walker 1993, pp. 77-85). However, perhaps a more relevant precedent - not in that it aimed to tell a narrative history, but in that it relied on the interrelationship between on air, online and onsite to foster engagement and participation in its subject matter, was The Big Dig, sponsored by Channel 4’s Time Team in 2003 (http://www.channel4.com/history/microsites/T/timeteam/). Nearly 8,000 members of the public volunteered for a week, participating in a vast cataloguing of archaeological activity in the UK. A website provided a hub for participants and the public interested in finding out more than was broadcast (Gaia et al. 2005).

Though A History of the World in 100 Objects was not a TV series, TV played an important role in the wider project. The main element of this was Relic: Guardians of the Museum, a 13-part series on CBBC (Children’s BBC channel for ages 6-16). Relic was filmed on set at the British Museum and in a studio. A mix of adventure and game show, a ghostly tour guide named Agatha (in a very 1920s tweed suit) guides three children (the contestants) on a quest to help her defeat the evil Dark Lord, whose servants - the ‘Dark Forces’ - chase them through the Museum. The children have one night to discover a relic in the Museum and on the way have to win three challenges, which consist of answering questions about a ‘vision’ revealed to them. If the children succeed in the final battle, they are awarded the golden scarab and become ‘Guardians of the Museum’. Failure condemns them to becoming relics themselves, trapped in the Museum forever. The objects used in Relic were all chosen from the 100 objects in the radio series.

Other TV programmes related to the project. On the night of the first radio broadcast, there was a Culture Show special, a one-hour show on BBC2 in which Neil MacGregor explained the concept of the programmes. Objects from Birmingham, the Isle of Man and Scotland were also featured, introducing the UK museum partnership component of the project. Other TV programmes were broadcast in the BBC English Regions during the course of the year, such as 12 10-minute features in the regular series Inside Out. Also, in the English Regions, 12 special A History of the World-inspired programmes were broadcast at 7.30pm on BBC One. For example, in the South West, Adam Hart-Davis presented a piece about a Baptist preacher from Dartmouth who discovered how to get energy from steam, and, in the North East, Stuart Maconie told the story of Calder Hall, the world’s first nuclear power station.

On BBC 2 Wales, there were 4 half-hour television programmes presented by Eddie Butler, and BBC Northern Ireland showed 5 one-minute films entitled A History of the World – Take One Object, each featuring one of the museum objects representing Northern Ireland in A History of World, starting with the Queen’s University Civil Rights Banner from the Museum of Free Derry. On BBC Radio Scotland, 6 editions of the Radio Café and 6 editions of Past Lives were dedicated to A History of the World.

3. A History of the World online

One of the main objectives of the project was to develop a digital platform to act as a hub for the activity and participation of museums and individuals. At its core, the website was developed to support and extend the radio programmes. Radio has one dimension, that of time, and demands incredible attention from the listener. The website allowed listeners to manage the demands of those 25 hours broadcast over 10 months – through what media consumers today increasingly expect to do – control of their consumption of media. On the site, visitors were able to subscribe, download or listen off the page to any of the broadcasts after their live transmission. The BBC’s usual 7-day limit on access to programmes online was waived for A History of the World in 100 Objects. The site visitor is also able to see what the objects looked like through photography (using deep zoom) and video of the objects in the round where relevant. This gave users the chance to get a closer view of the objects than is even possible in the gallery. Annotations explaining details of each object were revealed as the user zoomed in closer to a particular element.

The website then became the platform for the extension of the project to include objects submitted by museums across the UK as well as by members of the public, and encouraged participation through blog commenting and the project’s Facebook page. (http://www.facebook.com/ahotw)

At launch, the website included 585 objects contributed by 356 museums across 57 BBC regions to complement the 100 BM objects. Each BBC region had been asked to choose 10 museum objects that would tell the history of their part of the world from a local and global perspective. Northern Ireland, which counts as a single BBC area, contributed 25 items. By December 2010, around 1,500 objects had been contributed by 551 museums/historic sites. The project branding was used in a special label template for the objects on display in each museum.

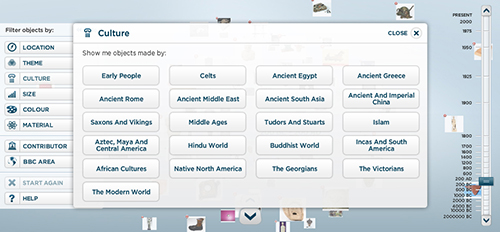

The main interface to the museum objects on the website was a Flash-based ‘Explorer’ (with an HTML complement). This allowed the user to browse the objects by time, theme, material, culture, origin, size and colour. Thus, as well as following the narrative set by the British Museum’s 100 objects, site visitors can initiate their own journeys, find objects related to their own historical interests, and view objects from museums and individual contributors side by side – an important element of the ‘democratisation’ ambition of the project. The notion that ‘every object tells a story’ was central to the educational aim of the series, to show that history can be told through objects, as well as to encourage museum visits and a new way of thinking about the things we own, either personally or collectively in our local or national collections.

Fig 2: Filter on the discover interface, A History of the World website

Fig 2: Filter on the discover interface, A History of the World website

Public participation

From launch, members of the public were also invited to upload details of an object in their possession, something that they believed told a global story analogous to the Museum objects. In order to maintain high quality and get contributions that adhered as closely as possible to the project’s editorial principles, clear parameters for the call to action were explained on general information pages of the website, in broadcast and on the object uploader form. The total number of objects uploaded by the public during the course of the project was around 4,000, which works out at about 0.1% of visits to the site. This figure could have been higher, but given the complex nature of the call to action, it is perhaps not surprising.

As well as contributing objects, the website offered other ways to engage. Each object page had its own comments thread. Partners and visitors to the site were encouraged to comment, to ask questions or to add more information to the existing descriptions. Curators from the British Museum were regular contributors. (a good example: http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/objects/I3I8quLCR8exvdZeQPONrw). The blog published over 100 features, many of which were written by curators and editors from the British Museum and museums across the UK. (for example: http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/ahistoryoftheworld/2010/01/weekly-theme-after-the-ice-age.shtml)

Suspense

Throughout the series, the 100th object had been kept secret, and a campaign leading up to the reveal was launched, to encourage appreciation of the contemporary nature of the themes woven through the programmes from the start, spark debate, and gain wider exposure for the project.

Five ‘contenders’ for the 100th object were published daily in the week preceding the final reveal, and featured on Radio 4’s breakfast news and current affairs programme, Today. Reaction to the contenders took coverage of the project to an even wider audience. The presence of a replica Chelsea FC shirt in the list of contenders saw A History of the World featured on the BBC Sports site and on several football fan sites, such as whoateallthepies (http://www.whoateallthepies.tv/chelsea/46529/didier-drogbas-chelsea-shirt-in-line-for-place-in-british-museum.html).

The identity of the 100th object was revealed live on air – and simultaneously on the website blog – on October 14th, one week before the broadcast of the final programme on Friday 22 October. The build-up to the announcement was given a lot of attention on the website, on social media channels, and on air. The public were invited to suggest an object that they considered represented life in 2010 (http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/get-involved/my100th). Over 800 suggestions for the 100th object were received, including responses from celebrities (some of which were video interviews). It also encouraged 70 comments on the site’s blog (http://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/ahistoryoftheworld/2010/10/100th-object-contenders-1.shtml). The call to action / messaging around the conversation that was published on the website, blog, Facebook and Twitter (using the hashtag #objectoftoday) clearly stated the limits of the request – the public were asked to tell the BBC and the British Museum what object they would select if they were given the task of doing so. The wording was careful: the Museum had already selected the 100th object; the public were not being asked to submit proposals that would be subsequently assessed by the Museum, and they were not being asked to vote for which of the 5 contenders they would prefer to see as the 100th object.

Fig 3: Suggestions for the 100th object, A History of the World website http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/get-involved/my100th/

Fig 3: Suggestions for the 100th object, A History of the World website http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/get-involved/my100th/

4. A History of the World onsite

The objects featured in the 100 radio programmes were on display in the Museum during the broadcast period and will remain on display until the end of the 2012 Olympics. A deliberate decision was taken not to bring the objects together in an ‘exhibition’, but to display them in the permanent galleries – thereby contextualising them within cultures so that they can serve as a jumping-off point to explore the wider collection. Many of the objects required some degree of intervention to enhance their visibility. The objects were all given an additional layer of interpretation so that each was presented within a global context. The A History of the World branding was also used in the graphics.

The objects were all annotated on to the museum’s floor plan so that visitors could easily find them. A ‘Relic trail’ of objects featured in the CBBC series was also created.

The project also had a physical component in the events (around 120 in total) that took place across the UK in 2010. These drew people to visit the objects in the participating museums, and contribute objects online. For example, in February 2010, over 50 A History of the World events were organised by museums and BBC teams throughout the BBC English Regions.

The event at the Museum of Canterbury in Kent for A History of the World drew more than 1100 visitors - five times the number they normally get. Visitors had heard about the event from a variety of sources: BBC Radio 4, Regional TV and local radio. Volunteers helped visitors to upload their objects, many of which were made into radio features during the course of the year. (Steven George, BBC Broadcast co-ordinator for BBC South East)

One particular focus for events was Museums at Night over the weekend 14-16 May, an annual initiative with late opening and special events in Museums across the UK and Europe (http://www.culture24.org.uk/museumsatnight). A History of the World partner museums screened an episode of Relic, and ran a Relic trail tailored to their museum and tied into the A History of the World website. Museums also used the event for talks and promotion of the display objects that they had included in the project.

Relic was also the focus of an initiative targeted at all UK schools that teach 7-11 year olds. To support teachers, BBC Learning produced a series of lesson plans aimed at Primary school students. These demonstrated how to use objects as a focus for teaching history, and featured 13 of the British Museum objects.

In August, the Relic Challenge was launched, to encourage schools to upload objects directly to the A History of the World website. The Relic Challenge Kit was a suite of lesson plans and resources based around A History of the World. The lessons culminated in the children choosing up to five objects to upload. The BBC then chose 20 objects from the submissions from across the UK that told particularly interesting stories, and invited the schools to make a short radio programme about their object with BBC radio staff, to be broadcast in early 2011 on the digital channel BBC Radio 7.

Perhaps the highest profile events that the project was involved in were the day-long location shoots of Antiques Roadshow, a TV series filmed at various locations around the UK (e.g. in the grounds of country houses and cathedrals) where members of the public bring in objects for appraisal and assessment by experts. Between May and September 2010, the project had teams at eight of these venues, including the British Museum itself. They canvassed people waiting in the queues for interest in the project, encouraging and assisting participation by taking photographs and providing templates for people to fill in details about the object that they had brought. The team then uploaded the details to the site.

5. Interplay among the media

Curators, listeners who had contributed objects to the site, and local historians appeared regularly on many of the BBC’s 61 local radio stations. Many stations ran documentaries that tracked their local history through the prism of objects uploaded to the website by museums and individuals. For example, BBC Guernsey broadcast an hour-long documentary about the history of the island on 4 April 2010. In Lancashire, Sally Naden presented her show live from the Harris Museum & Art Gallery in Preston in February 2010. Making History and Tracing your Roots on BBC Radio 4 regularly included contributors and their stories on their programmes.

BBC Radio 4 also broadcast short trails featuring some of the most fascinating objects uploaded by the public to the website. These mini features (broadcast in two tranches of 16) included the contributors themselves describing their objects and were made by the same unit that made the core series, A History of the World in 100 Objects. These mini features completed a ‘virtuous cycle’, whereby a core series had inspired audience contributions, that in turn became the subject of additional broadcasting. It has long been an ambition of the BBC to use its presence across media to generate content in the digital space that will be reflected on air. This is a rare example of that aspiration being realised.

The stories told through some of these objects were fantastic. Robert Walters talked about a hammer worn to fit the hand of the cobbler, Samuel Revill, who used it for a lifetime’s labouring. Mary Singleton’s Young Farmer’s badge from the 1950s was another object telling the story of hard labour, this time by the farmers in the post-war period who responded to a nation’s call for self-sufficiency. The full list of objects, with audio, can be found at http://www.bbc.co.uk/ahistoryoftheworld/get-involved/audience-stories.

Effects

Usage and engagement statistics on the BBC A History of the World website show clear indication of the effect of the broadcast programmes. The total number of visits (worldwide) to the site was on average 2.3 times higher during the 20 weeks when the programmes were broadcast, compared to the 20 weeks of the two off-air periods between the 3 series. The number of unique users of the blog was 4.5 times higher during broadcast weeks; the average length of visit to the site was 54 seconds longer (at 04:50s), and the number of pages per visit also higher -not surprising, perhaps, but an indication of the inter-relation between on air and online. However, the digital offer created a life of its own beyond the broadcast: user figures while the series was off air were much higher than is the norm for BBC programme-related sites. The programmes are still being accessed online in early 2011, months after the final broadcast on Radio 4.

6. Structure

From the start, the project team structured the ‘information reveal’ to ensure that the programmes led. The site launched on 18 January 2010 , the day of the first programme broadcast on Radio 4, revealing the identity of all 99 objects to the public for the first time. At launch, only the first 30 objects (those in the first series) had the full set of content, with the other 69 only represented by a title and a single image. As a web offer this may have been something of a drawback. Users do not normally expect data to be withheld. The team feared a backlash from users in this regard, but criticism of this element was almost non-existent.

Each object page on the A History of the World website has a link to more information about the object on the relevant Museum site. On the British Museum site, this was the ‘Highlight’ page, with a longer narrative description, images, suggested further reading, links to related highlighted objects and other pages on the British Museum site, including the relevant object record in the collection database. They also contained a call to action to ‘listen to the programme’, with a reciprocal link to the relevant page on the A History of the World website.

There were around 52,000 referrals to the British Museum website during the period of the broadcast, 66% more than during the same period in 2009. Referrals from the BBC accounted for around a quarter of the traffic to the British Museum’s 100 object pages, which increased 227% compared to the same period in 2009. However, while during this period, traffic volume to the BM site as a whole was 16% higher than the previous year, the volume of referral traffic (from all sites) to the British Museum site only rose 4%. By comparison, search engine traffic was 23% higher and direct traffic period 11% higher during the broadcast period compared with the previous year. What is evident from this, and a more detailed look at a range of keywords that drove traffic to the British Museum site that was obviously related to the objects featured in the series, is that while many people followed the calls to action on air, on posters and other marketing material, many instead used a search engine to look for keywords that they had heard in the programme and came directly to the British Museum site. A single example here gives an idea of the aggregated effect:- during the period of the broadcast, 1667 visits to the British Museum website started with a Search Engine search for ‘swimming reindeer’, whereas only 20 did in the previous year.

The principle of encouraging and achieving this sort of journey between two sites represented an innovation for both the British Museum and the BBC. For the Museum to present its content so comprehensively on another website in another domain was a risk to its own web traffic. The British Museum’s presence in a co-branded area of the BBC’s website had never happened before, and while the BBC is committed to external linking, the scale of this as implemented for A History of the World was unusual.

7. A new form of partnership

Crucial to the success of the project was a set of objectives that were shared by the partners. The activities of all parties were measured against the same aims for which all were accountable. This was unusual in that traditionally the needs of the museum would not be such a direct interest for the broadcaster, and in turn, the museum’s contribution would have been more focused on serving its need for a broadcast platform from which to engage both new and existing audiences. A new way of working together was established.

The partnership was not simply one forged in Central London. If the ambition to maintain the editorial concept behind the selection and treatment of the 100 British Museum objects with those contributed by the UK partner museums succeeded, it was down to the collection of individual relationships established between museum staff and the staff in BBC regional teams in their area. A ‘buddy’ system was established, with the BBC providing the partner museum with support for the technical and editorial aspects of the upload of their objects to the A History of the World website. In addition, this pairing was then able to assess public contributions from that area that would make good broadcasts on the BBC regional channels, and develop them together. The buddy relationship was intended from the beginning to extend beyond the lifetime of the project.

The BM was in a position to help facilitate introductions and relationships through its existing Partnership UK Programme, while the BBC’s Voices project of 2006 (http://www.bbc.co.uk/voices) provided a broadcast model. This was a year-long examination of English as spoken around the UK, and involved a central spine of programming on BBC Radio 4 with related programming on all the BBC local, regional and national stations, supported by educational activity with schools.

The BBC has committed itself to a significant increase in the scale of its partnership activity, particularly with other public bodies. Launching the corporation’s strategy Putting Quality First (March 2010), the BBC Director General Mark Thompson said, ‘We want partnership to be the 'default' setting for everything new we do’. (http://www.bbc.co.uk/pressoffice/speeches/stories/thompson_ft.shtml)

A History of the World has been a beacon or pathfinder project in realising this strategy. The BBC and museums have worked together many times before. Landmark series have been made with access granted by institutions for the BBC’s cameras such as in The Museum of Life (a series of 6 programmes, first broadcast March-April 2010) at the Natural History Museum (http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00rp1w0) and many programmes are routinely made about exhibitions. What seemed to distinguish the collaboration for A History of the World was the balance in the partnership, with two institutions committed to a single, jointly executed editorial idea. In this partnership, the key objective was enshrined in the editorial idea ‘to tell history through objects’ and encourage a national conversation around that enterprise.

The challenge for both organisations was to be able to share expertise and assets in the pursuit of that idea. The nuance here may be subtle, but it is significant. The norm would have been the broadcaster using the museum to supply content and the museum using the broadcaster to supply ‘profile’. In this partnership, those outcomes were a bi-product rather than an end in themselves. This thinking may be the most significant long-term legacy of A History of the World. Evidence for this approach lay in a number of activities. Programme scripts were written by the Museum, though edited and produced by the BBC, which had final editorial control over the broadcasts. The website was built on the BBC’s platform and funded by the BBC, but the taxonomy and the user interface were devised together and signed off jointly. Images and data on the website remained the copyright of the museum, but were licenced to the BBC by the museum at no cost.

The initial agreement by both parties that this was to be a public service partnership in which neither side sought any financial reward was perhaps the single defining element that made the project possible. The arrangement has a simplicity and clarity that smoothed the rest of the relationship and was reflected in the highly successful partnerships with museums and BBC Local Radio and Television across the UK that will last beyond the project itself.

8. References

Gaia, G., et al. 2005, Cross Media: When the Web Doesn't Go Alone, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2005: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 31, 2005 at http://www.archimuse.com/mw2005/papers/gaia/gaia.html

George, Stephen. BBC Broadcast co-ordinator for BBC South East. Feb 2110.

Walker 1993. John A Walker, Arts TV, A history of arts television in Britain, John Libbey, Arts Council of Great Britain, 1993