Introduction

In her landmark book, From Knowledge to Narrative, Lisa Roberts (1997) analyzes a paradigm shift in late-20th-century museum exhibitions in which museums moved from traditional methods of knowledge transmission to constructivist interpretive methods such as narrative. Today, museums wishing to adopt game-based learning methods face a similar challenge: to move from now-familiar narrative methods to a game-based approach. A game, as defined by Salen and Zimmerman (2004), “is a system in which players engage in an artificial conflict, defined by rules, that results in a quantifiable outcome." Rules, rather than narrative, are the heart of a game. They create the space for player interactions while defining the consequences of every action. As a result, applying a strong narrative to a game usually results in neither a good story nor a good game. Instead, we must adopt a true rules-based design that gives players real control over the arc and outcome of their experience. This approach, however, requires designers and educators to dig into the content to find a few rules inherent in the subject matter that can then define the gameplay.

This shift from narrative to systems is less formidable than the shift from knowledge to narrative that Roberts describes. The old paradigm defined knowledge as a product: an objective, verifiable truth. In contrast, both narrative- and game-based learning are rooted in constructivism, the notion that learning, as Hein (1998) says, “is not a simple addition of items into some sort of mental data bank but a transformation of schemas in which the learner plays an active role and which involves making sense out of a range of phenomena.” Roberts' use of the term "narrative" echoes Hein's definition. She describes it not as merely a story but, drawing on Jerome Bruner's work, as "…the creation of a story. It aims to establish not truth but meaning; explanation is achieved not through argument and analysis but through metaphor and connection." (Roberts, 1997) Learners create their own narrative – a unique and highly personal explanation or understanding of any given experience.

Whatever the narrative that learners create, it will inevitably differ from what museums present to them. To properly engage that meaning-making process, museums must acknowledge that the messages we present are merely one possible version of the truth, while encouraging alternate arguments and perspectives to create fertile ground for constructive meaning-making. "This," says Roberts (1997), "is the essence of education." And in recent times, museum professionals have embraced constructivism, developing onsite and online offerings that frame information and messages in social and cultural contexts, offer multiple perspectives, and challenge visitors and users to make their own sense of the content. Museum researchers, studying those physical and virtual visits, have found that learning does happen in highly personal, and sometimes profound, ways. (Falk & Dierking, 2000; Borun, 2007)

Almost by definition, games are designed to be constructivist experiences. The system that a game presents to the player represents a particular model of reality. The player must explore it, push against it, and analyze how it works – and, in the process, come to understand the nature and meaning of success within the game context. The player’s experience derives from the underlying system of rules, which in turn represents the game developer's perspective on the world. The player, in effect, is exploring some corner of the designer's mind to understand the rules of this constructed game-world.

Despite the fundamental role of rules in games, it can be difficult for museum educators, particularly those schooled in the humanities rather than science, to adopt this game-system approach. Exhibits and educational materials generally explore the idiosyncrasies of a given topic, be they the expressive aspects of an artwork or the narrative arc of an historical event. These methods typically use narratives, such as personal accounts presenting multiple perspectives, to stimulate (and simulate!) meaning-making by visitors. This approach can be powerful, but with digital media we often strive to make these narratives interactive in a functional as well as cognitive manner. And indeed, an interactive narrative displays many desirable features of a constructivist learning experience – but it is often less than the sum of its parts. We must recognize the severe limitations of this approach before we can fully appreciate how a rule-based system overcomes them.

The perils of interactive narrative

Storytelling is a creative learning experience: the teller is constantly discovering new facets of the characters, themes, and plot, and accommodating those insights into the evolving story. Reading a story is also creative; as literary critic Wolfgang Iser (1981) says, "the reader 'receives' a text by composing it." So if readers are naturally rewriting the text in their minds, why not give them real authorial power? In digital media, we can make storytelling a genuine collaboration that embraces the reader perspective. Inspired by game designer Sid Meier's famous definition of a good game as "a series of interesting choices" (in Rollings & Morris, 2000, p. 38), we might use a "choose your own adventure" branching story design. This approach should serve the idiosyncratic arc of a real-world narrative while also providing the meaningful choices so critical to a game. Players evaluate each situation, consider the choices, and steer the story in their preferred direction.

In practice, though, this approach serves both story and gameplay poorly, as it forces players into increasingly meaningless choices simply to keep the number of story branches manageable. We might initially map out the game choices and consequences like this:

Fig 1: A Simple Branching Narrative

Fig 1: A Simple Branching Narrative

After just four decisions, we have 24 branches, each of which must be researched, written and produced. Yet all this work results in just a few minutes of game time for the player. So, inevitably, we must simplify. We might do so with a sequence of right/wrong decisions, feeding the latter back into the correct path:

Fig 2: A Branching Narrative of Right/Wrong Choices

Fig 2: A Branching Narrative of Right/Wrong Choices

While this design still offers choices, they are of the most basic kind: quiz questions that force players to follow a single path. Players quickly realize that their choices are inconsequential: they have no effect in the game and thus it requires little thought.

We can get more creative and make decisions point to a smaller set of branches, so we have perhaps just four branches after four decisions.

Fig 3: A Practical Branching Narrative

Fig 3: A Practical Branching Narrative

This improves on the simple right/wrong branching, but it still reduces player's agency and diminishes the significance of each decision. Clever design may help conceal this fact to players, but over the course of a 30-minute game, it is extremely hard to sustain a sense of genuine choice and consequence. Furthermore, the choices provided are not necessarily the choices that the player would have chosen. By scripting these choice-paths, we are imposing our own version of the narrative on the player, depriving them of any legitimate authorship of their experience.

Freeing the player with rules

Games solve this quandary with a system of rules. The players' actions function as inputs into the system; the rules evaluate those inputs and modify the current game conditions accordingly. Even a simple ruleset can create complex and exciting gameplay, freeing players from the scripted predictability of a branching structure.

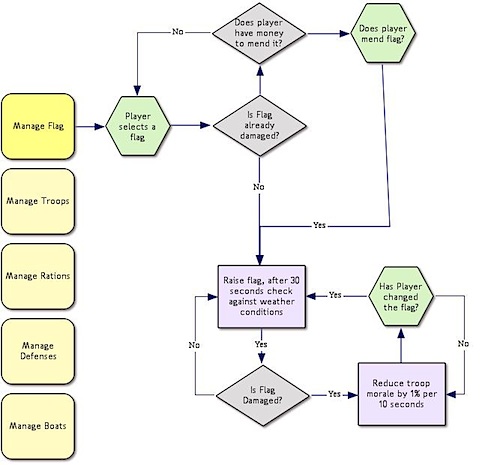

For example, the flowchart below shows a subset of rules from a game we are developing about the bombardment of Fort McHenry during the War of 1812. The player must manage a variety of resources to keep troop morale high during the bombardment, including the U.S. flag flying over the fort. Players can select from several sizes of flag (the larger the flag, the more it boosts morale), but wind and rain can damage the flag (the more intense the weather, the greater the damage). By writing a few rules to manage these choices and their consequences, we create a self-sustaining subsystem that, along with other subsystems, creates lively and challenging gameplay.

Fig 4: A flowchart of game rules

Fig 4: A flowchart of game rules

What the player is doing while interacting with these rules is the game's core dynamic. This – not the topic, not the content – is what the game is really about. It’s what players spend most of their time doing – and thinking about how to do it well. A great game has a core dynamic that is easy to understand, hard to master, and endlessly engaging. The core dynamics of most games can be described succinctly, as with these examples by Braithwaite (2008):

- Risk: Territorial acquisition

- Tetris: Spatial reasoning

- Pac-Man: Evading

- Bejeweled: Pattern matching

- Call of Duty: Destruction

In any game, the players’ actions must be highly stereotyped, because a complex core dynamic would make the game's learning curve impossibly steep. So, to an observer unfamiliar with a game, the players' actions appear simple, repetitive, and quite often boring: roll the dice, move the token, swap the jewels, shoot the opponent. But to the player, they are intensely interesting. Game conditions are constantly changing, requiring careful evaluation of the situation and concerted thought about when, where, and how to act next. Success depends on how well the player understands that underlying system of rules. As they probe the system, evaluate the feedback, revise their understanding, and probe again, players are indisputably learning. Is there a better description of stimulating gameplay than Hein's (1998) definition of constructivism? In his words, it is “A transformation of schemas in which the learner plays an active role and which involves making sense out of a range of phenomena.”

In the first episode of WolfQuest (http://www.wolfquest.org), a wolf simulation game that we developed with the Minnesota Zoo, the core dynamic is hunting: tracking, chasing, and killing elk. Aside from a few introductory tips, the rules of this dynamic are not explained at the start of the game. Players must try hunting for themselves, see how the elk respond, and modify their behavior accordingly. In the summative evaluation (Haley Goldman, Koepfler, & Yocco, 2009), one player described how she responded to these rules:

My wolf was not the fastest but had reasonable stamina and was very strong. I tried several things like quickly trying to kill the elk, or lunging and resting, going for it then cutting it off as it tried to get back to the herd. I would pick out a weak elk and once it was far enough away from the herd I would isolate it and lunge. When I lost energy I would rest letting it head back to its herd but once I had the energy, I would cut it off before it could. Staying at a far enough distance to rest allowed me to know where it was heading and lunge at it from there. When my mate came along, I noticed he was faster. To test this challenge, it was more me observing his reaction to the elk and my attacks and developing how they could work together. The technique changed to me picking the elk and lunging first, when I lost energy he would chase it down sapping its strength until it was slow enough for me to go and make the killing blow.

As they master the hunting mechanic, players make sense of the game-world, drawing conclusions from their experience and often generalizing from the game to the real world of wolves. Here are a few comments from players about what they learned from the game (Haley Goldman et al., 2009):

I can understand why wolves (and dogs) scarf up every single bite of food. They don't know when they will be able to eat again, as I’ve learned it's tougher than we think to catch a stupid elk, they kick back, HARD.

Hunting is actually quite difficult. Wolves have to contend with other predators. Wolves don't always eat their entire kill.

Wolves have to eat alot in order to live. [They] look for weak prey. A wolf can survive on an elk for days.

WolfQuest players often used critical thinking skills such as trial and error, model- and system-based reasoning, testing, and prediction to understand the game better and improve their gameplay strategies. Education scholars like James Paul Gee see this thinking process as a core value of games. Gee (2003) describes it as a four-step process: probe, hypothesize, reprobe, rethink hypothesis:

Some consider this four-step process to be the basis of expert reflective practice in any complex semiotic domain. But it is also how children learn when they are not learning in school…. [It] is central to how humans, as biological creatures of a certain sort, learn things when learning is essential for survival and for thriving in the world.

Stimulating social interaction, both real and illusionary

The rules not only define the interaction space within the game world. They also define the interactions between players. Historically, nearly all games have been social, multiplayer activities. It was only with the advent of computers a few decades ago that single-player games become common – and already, with the rapid growth of the Internet, multiplayer is reclaiming its pride of place among computer games. The social experience is central to games: it’s much more challenging and satisfying to outwit a human opponent than a computer AI. The social element is also central in meaning-making, as revealed by research into family learning in museums. In fact, board games meet many of the characteristics of family-friendly exhibits (Borun et al., 1998): they are multi-sided, multi-user, multi-outcome; they present readable text, and many are accessible to both children and adults. Board games also generate conversation, a key factor for learning. (Borun; Falk & Dierking, 2000) With careful design, our game rules can provoke both face-to-face and online conversations about content, context, and meaning.

Of course, single-player games are not going away, and sometimes, for practical or content reasons, they are the best approach for certain topics. When the core dynamic enables each player to seek the same thing using the same means, the game is symmetrical and well suited for multiplayer. But when players have asymmetrical goals or methods, the game requires a radically different design – or a single-player approach. For example, the bombardment of Fort McHenry was so one-sided (the British bombarded the fort; the Americans hunkered down and withstood it) that we could not envision a viable multiplayer mode for our Hold the Fort game. But even without other real people in the game, players develop a relationship with the game characters, situations, and rules, much like TV viewers develop illusionary or ‘parasocial’ relationships with television characters or personalities. Psychologists call this ‘social surrogacy,’ when people “use technologies, like television, to provide the experience of belonging when no real belongingness has been experienced.” (University of Buffalo, 2008; Derrick, Gabriel, & Hugenberg, 2009) We can tap into this same phenomenon to engage social needs of players, even in a single-player game.

Reality – but according to whose rules?

The core dynamic thus determines what kinds of thinking players engage in as they interact with the game. It also reveals which version of reality the designer has chosen to present. For game systems, just like knowledge, are social constructions. The ruleset reflects the values, beliefs and assumptions that the designer has (consciously or not) built into the game. For example, some people object to the violence in first-person shooter games, fearing that it encourages violence in the real world. But in terms of the values expressed by rules, what’s perhaps more salient is that players have many ways to kill but no way to talk to each other – dialogue ends when these wargames begin. Of course, this is no different from chess, where players can ‘capture’ game pieces but not negotiate with their opponent. Indeed, every game restricts players to an artificially narrow set of actions. In five-card draw poker, players can obtain new cards only from the deck, not by trading with each other. In Tetris, players can only rotate and move blocks, never reshape them. In Monopoly, players collect rent from each other but cannot donate to a homeless shelter.

Games like poker and Tetris do not purport to represent some aspect of the real world, but many games do: Pit represents commodity market trading, SimCity represents urban planning, Call of Duty represents an infantry soldier's experience of war. In such games, the designer's own worldview can affect the choice of rules. Often this is an overt goal. As Roberts (1997) says, "Museums are legitimately engaged in the production of a story and…they may legitimately present a story that presents their particular interests and goals." So too do game designers embed their ideas about the world in their rules. In 1860, American board game pioneer Milton Bradley broke from tradition with his radical game, The Checkered Game of Life (later shortened to The Game of Life). Previously, board games were concerned entirely with moral virtue, but Bradley’s game defined success in secular business terms, “depicting life as a quest for accomplishment in which personal virtues provided a means to an end, rather than a point of focus” (Milton Bradley, n.d.). Monopoly was based on an earlier game designed by Elizabeth Maggie, a Quaker, to illustrate the negative aspects of land monopolies (The Landlord Game, n.d.). Fable, a computer role-play game (RPG), features a morality system where the appearance and attributes of your avatar change based on where your actions fall on a moral continuum.

The goal for developers of learning games, then, is to design rulesets that present their particular version of reality – while also acknowledging that this is only one such version. At times, players will naturally critique the assumptions made by the rules, as many did with the Fable RPG series, which equates goodness with physical beauty. Do a good deed and your avatar becomes more attractive; do something evil and it becomes uglier. As game critic Jeffry Matulef (2010) notes, this rule misses an opportunity to subvert a widespread cultural bias and create more interesting choices for players:

Given my vanity regarding Fable 2 characters, I think it would have been infinitely more fascinating if being good made you uglier while being evil left you pretty…. For example, somebody could be trapped in a burning building. If you let them die, you maintain your good looks. If you save them, you suffer permanent burns over much of your body. You could even have certain romantic subplots that could no longer be pursued after such horrible scarring.

Similarly, SimCity has been criticized for the assumptions in its model of urban development, most memorably by Sherry Turkle, when quoting a 10th-grader: "Raising taxes causes riots." Turkle added, "If I had programmed [SimCity], raising taxes would’ve led to more social services and greater social harmony." (Fischman, 2009). Perhaps some future version of SimCity will add an interpretive layer in which TV pundits debate the effects of raising taxes. But even then, the actual impacts will be determined by the designer alone.

Typically, though, players do not question the rules. Instead, they internalize them in order to play the game well. Indeed, that is a central tenet of the "Magic Circle" – the notion that games and play are where “a new reality is created, defined by the rules of the game and inhabited by its players” (Salen and Zimmerman, 2004). Creating a game that encourages players to both adopt and critique its rules is a formidable design challenge, since it could easily break the suspension of disbelief that most games strive to create. But as James Paul Gee (2003) argues, this type of critical thinking can be stimulated either by the game itself or by other people, players and non-players:

If these people encourage reflective metatalk, thinking, and actions in regard to the design of the game…. And indeed, the affinity groups connected to video games do often encourage metareflective thinking about design, as a look at Internet game sites will readily attest.

Just as with museum visits, learning from games is facilitated by social interaction. Game designers should, as Falk and Dierking (2000) advise museum professionals, "create opportunities for group dialogue that extend beyond the temporal limits of the initial experience.

Further complicating matters is the difficulty of reducing complex phenomena to simple rulesets, especially when those phenomena are not fully understood even by the experts. In WolfQuest, we thought about adding bison as a prey animal for wolves, but biologists do not yet fully understand wolf-bison relations in Yellowstone. This made it difficult to create clear, simple rules that are also scientifically accurate. Game rules don't allow us to gloss over uncertainty with phrases like “we may speculate” or "the data suggests." We must make our best guesses and formalize them in the ruleset, even though this may convey to players that we know more about that phenomenon than we actually do.

Not just learning, but learning about our stuff

Much of the academic interest in games in the past decade has focused on ways that games foster literacy, critical thinking, and problem-solving (Gee, 2003; Barab, Gresalfi, & Arici, 2009; Squire & Jan, 2007). While museums certainly value these skills, the pressing question is how to make games that foster learning about our stuff: people, places, things, theories and phenomena. That's what we want players to know about. Games may seem like inefficient ways to share that information, but as Gee (2005) notes:

"Know" is a verb before it is a noun, "knowledge." And something very interesting happens when one treats knowledge first and foremost as activity and experience, not as facts and information – the facts come to life. Facts become easier to assimilate if learners are immersed in activities and experiences that use these facts for plans, goals, and purposes within a coherent knowledge domain.

This, of course, is what games do well. Information is not assimilated as an abstract body of knowledge, but in an immediate, "need-to-know" context. While I normally have no reason to know or care about the price of tea in China, if I need that information in order to achieve my in-game goals, it becomes both relevant and meaningful information.

My firm recently worked with the USS Constitution Museum to develop the A Sailor's Life for Me website about that ship, aka Old Ironsides, featuring the game Sail to Victory (http://www.asailorslifeforme.org). The picaresque life of a nineteenth-century sailor seems ripe for an interactive story, but given the structural and practical limitations of that format, we instead sought to design a game system – and quickly realized that naval life was indeed regulated by rules. Highly regulated, in fact. The daily schedule determined what each sailor should be doing at any given moment of the day – and what the punishment would be for anyone avoiding his assigned duties. Furthermore, a promotion system created goals, rewards, and consequences for all sorts of sailor actions. An unwritten yet strict code of conduct regulated social interactions among sailors, determining each one's popularity and social standing. And finally, each sailor was naturally affected by physical and psychological rules – the need for food, drink, self-respect and pride – which determined his own health and happiness.

These intertwining rulesets became the game's core dynamic, which we might call "Improvement." With every action, the players seek to improve their situations by earning promotion, popularity, and health & happiness points. Quite often, though, these three goals are at odds. Tattling on a messmate earns promotion points but subtracts popularity points. Playing a game of dice increases popularity while running the risk of being caught by an officer and losing promotion points. Sharing chocolate or other treats with a friend gains popularity at the expense of health and happiness. Almost every decision involves tradeoffs. Thus, the players’ characters takes shape based on their choices. Are you focused on promotion at any cost, or are you a hale-fellow-well-met type who proceeds through the ranks more slowly? Do you take care of yourself first and foremost or try to balance the demands of officers, messmates, and their happiness? The game arc is simultaneously shaped by both these rules and the players' actions and choices. Players can't help but learn something about a sailor's life, yet the meaning made is their own, not dictated by the museum.

Fig 5: A decision in Sail to Victory game

Fig 5: A decision in Sail to Victory game

Virtual skills and real learning

The Sail to Victory game is much more than a series of choices. Each "day" in the game is filled with tasks – mini-games – that give players a taste of daily life aboard Old Ironsides. Each mini-game draws on common game-playing skills: timing, dexterity, memory, and targeting. These skills are familiar to players from both games and the real world, so they require minimal instruction. It was tempting to use these mini-games to teach new skills to players, such as tying knots, setting the sails, and preparing food. Those are, after all, interesting aspects of the subject matter. But these skills require substantial instruction while offering little subsequent play value – a fatal combination in a game. Instead, we matched familiar skills with typical shipboard tasks. Many of these mini-games involve dexterity and timing to evoke the mental and physical demands of a sailor’s duties: scrubbing the deck, delivering powder to the gun deck, whacking rats in the hold, and steering the ship. Others employ a Simon-like sequence of actions to represent such esoteric knowledge as loading cannons and setting the sails. And given the subject matter, a few tasks employ a standard game trope: aiming and firing weapons. Thus, the learning goals for each mini-game are narrowly construed, but in aggregate they encompass many of a sailor's on- and off-duty activities.

For example, the Officer's Servant mini-game requires players to get their sea legs (virtually at least) by walking the length of the rolling ship – while carrying a full chamberpot. To prevent spills, the player must tilt the pot to counteract the motion of the ship. By employing real skills of timing and dexterity, we can create a virtual skill of sea legs (while emphasizing just how lowly the player-character's status is).

Fig 6: Officer’s Servant mini-game in Sail to Victory

Fig 6: Officer’s Servant mini-game in Sail to Victory

Just as rules help us avoid the pitfalls of branching narratives, they also steer us toward virtual skills that evoke, rather than replicate, real skills. Sometimes, though, we cannot find a good match between real and virtual skills. Knot-tying, for example, is an important skill for sailors, but we could not find a simple yet representative analog among common game skills. Nor did we want to create a laborious step-by-step tutorial that taught actual knots. So we left knot-tying out of the game – not a critical omission, but regrettable. The danger, of course, is excluding topics purely for design reasons, giving players an unrepresentative picture of the subject matter.

One ruleset to ring them all?

The rules of a game should give players a great degree of control over their fate, for agency is one of the prime attractions of a game. Without agency, games provide little relief from real life, where many factors outside our control affect our fates. But this design requirement can collide with the need for content integrity. A young sailor aboard Old Ironsides had essentially no control over the ship's success or failure during battle: it took 450 sailors working together to affect that outcome. For that reason, players in our game can determine their own character's progress but not the outcome of the battles, which are won or lost in the game whether the player performs well or poorly.

Such is the situation with many history topics that focus on ordinary people, where, as designers, we must somehow make the players’ choices truly consequential. This can prove especially difficult with topics like slavery where much of the point is an individual’s lack of agency. Such games must be designed very carefully to convey the historical reality while creating a satisfying experience for players. Players are more likely to blame the game for a frustrating outcome than recognize the unyielding accuracy of their experience.

This issue affects games on other subjects as well. Many science educators had high hopes for using Will Wright's game Spore to teach about evolution and biology, but the game disappointed by sacrificing accuracy for satisfying gameplay:

The snag is that Spore didn't just jettison half its science – it replaced it with systems and ideas that run the risk of being actively misleading. Scientists brought in to evaluate the game for potential education projects recoiled as it became increasingly evident that the game broke many more scientific laws than it obeyed. Those unwilling to comment publicly speak privately of grave concerns about a game which seems to further the idea of intelligent design under the badge of science, and they bristle at its willingness to use words like "evolution" and "mutation" in entirely misleading ways. (Robinson, 2008)

Commercial games, of course, have the liberty to make such design decisions, while learning games must serve the dual masters of fun and accuracy. While developing WolfQuest, for example, we ignored countless requests from players to add collectable items (a standard feature of role-playing games), such as these ideas suggested by one girl:

kill and eat 5 of different types of fish for a bundle of hay for a bed

kill and eat 5 elk for ancient cave paintings (if you have watched ice age the little stick figures of people and different animals) (but keep them only on one wall)

kill 1 hare for lucky rabbits paw hanging on the wall with charms dangling around it

kill 2 coyotes for Indian charms and a totem pole

kill a beaver for a miniture water hole (never dries out)

kill 1 human and avenge your forefathers death and retrieve the rare Ethiopian wolf skin

kill 10 bears to unlock a sasquatch creature (my brother made it up)

[comment by "jade" on WolfQuest Developer's Blog, June 29, 2007 (http://wolfquest.org/wordpress/?p=15)]

Of course, our accuracy goals didn't prevent us from letting players re-spawn after their wolf avatar died from hunger or injuries. Some game requirements are overruled at your own risk – which makes the decision made by the designers of the U.S. Army's game, America's Army, all the more notable: If you shoot your instructor, your avatar is thrown in jail….and remains in jail until you quit the game and start over. Sometimes the point to be made outweighs the need for satisfying gameplay.

Like it or not, they're making meaning!

By now it should be obvious that games present a significant design challenge for museums. Finding the rules intrinsic to the content, making one's perspective apparent but not too privileged, minimizing misinterpretation…it makes one ask, why bother? Why not just explain the material as clearly as you can? As the director of education at a large museum exclaimed in frustration to me some years ago, "Why does learning have to be a game? Why can't learning just be learning!” The problem, of course, lies in one's definition of learning. Our audiences are not absorbing information like patients injected with a vaccine. Whether we like it or not, they are constantly reshaping the information they take in, filtering it through their own values, perceptions, and experiences, actively interpreting and making their own meaning.

With a game, we explicitly recognize players’ participation. Indeed, we embrace it. A story might be complete without a reader, but a game is nothing without a player. With a game, we give our players a proper role, a legitimate share in the authorship of the experience. Certainly we forsake some control, but no more so than with more traditional narrative interpretation. We devise a handful of rules that define a system of interaction, a mini-worldview, and then hand the reins to them. Make of this what you will. Do with it what you can. The experience you make is your own.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to the many museum colleagues with whom I have worked over the years for helping me think about and experiment with the ideas discussed in this paper. I would particularly like to thank Frances Burroughs, Susan Edwards, Jennifer Eifrig, Kate Haley Goldman, Jaime Harold, and Sarah Watkins for their insightful comments and suggestions on drafts of this paper.

Screenshots from "A Sailor's Life for Me!" website courtesy USS Constitution Museum: illustrations copyright Stephen Biesty 2010.

References

Barab, S., M. Gresalfi and A. Arici (2009). “Why educators should care about games.” Educational Leadership, 67(1), 76-80.

Borun, M., J. Dritsas, I. Johnson, N. Peter, K. Wagner, K. Fadigan, A. Jangaard, E. Stroup, and A. Wenger. (1998). Family Learning in Museums: The PISEC Perspective. Philadelphia: The Franklin Institute.

Borun, M. (2007). “RACE – Are We So Different? Summative Evaluation of the Website”. Retrieved from http://informalscience.org/evaluation/show/188

Braithwaite, B. (2008). Challenges for Game Designers. Mansfield, Massachusetts: Charles River.

Derrick, J.L., S. Gabriel, and K. Hugenberg. (2009). “Social surrogacy: How favored television programs provide the experience of belonging.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(2).

Falk, J. H., and L. Dierking (2000). Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning. Walnut Creek, California: AltaMira Press.

Fischman, J. (2009). “Simulations May Be Causing Real Trouble.” The Chronicle of Higher Education, March 13, 2009. Consulted December 28, 2010. http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/simulations-may-be-causing-real-trouble/4573

Gee, J.P. (2003). What Video Games Have to Teach Us about Learning Literacy. New York: Palgrave/Macmillan.

Gee, J. 2005. “What would a state of the art instructional video game look like?” Innovate 1(6). Consulted December 28, 2010. http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=80

Haley Goldman, K., J. Koepfler and V. Yocco. (2009). WolfQuest Summative Report.

Hein, G. (1998). Learning in the Museum. London: Routledge.

Iser, W. (1981). The Act of Reading: A Theory of Aesthetic Response. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press.

Matulef, J. (2010). “Analysis: Altered States – Moral Choices and Character Design.” Gamasutra. Consulted on January 23, 2011. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/30501/Analysis_Altered_States__Moral_Choices_and_Character_Design.php

Milton Bradley. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Consulted December 27, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Milton_Bradley

Nieborg, D. (2008). “Morality and ‘Gamer Guilt’ in Fable 2.” Valuable Games. Consulted December 27, 2010. http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/games/2008/11/19/morality-and-gamer-guilt-in-fable-2/

Roberts, L. (1997). From Knowledge to Narrative. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books.

Robertson, M. (2008). “The Creation Simulation.” Seed. Consulted December 27, 2010. http://seedmagazine.com/content/article/the_creation_simulation/.

Rollings, A. and D. Morris. (2000). Game Architecture and Design. Scottsdale, Arizona: Coriolis.

Salen, K., and E. Zimmerman. (2004). Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. Cambridge, Massachusetts.: MIT Press.

Squire, K. and M. Jan. (2007). “Mad City Mystery: developing scientific argumentation skills with a place-based augmented reality game on handheld computers.” Journal of Science Education and Technology, 16(1), pp. 5-29.

The Landlord Game. (n.d.) In Wikipedia. Consulted December 27, 2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Landlord%27s_Game.

University of Buffalo (2008). “A Warm TV Can Drive Away Feelings of Loneliness and Rejection.” Consulted January 25, 2011. http://www.buffalo.edu/news/10063.