The Future of Digital Interpretation: Gallery Objects as Service Avatars

Fiona Romeo and Lawrence Chiles, National Maritime Museum, UK

http://rmg.co.uk/collections

Abstract

This paper outlines how digital technology in physical spaces can offer a seamless experience centred firmly on the object. Museums could reveal more of their collections by producing dense displays of objects with limited fixed interpretation but with hooks into deep digital services and invitations to participate. As computer vision brings the possibility to refine this interaction and make it more magical, the object itself can be a “service avatar”: all of the evocative power of an object, used to access digital experiences.

Keywords: archives, collections, objects, interaction, interpretation, augmented reality, mobile

In 2011, the National Maritime Museum (Museum) was transformed by the Sammy Ofer Wing, a capital-build project that doubled the usable volume of the Museum’s south-west wing and sensitively introduced a contemporary aesthetic. As part of this project, 1,000 cubic meters of archival material moved to the new wing, enabling the Museum’s Caird Library to dramatically reduce collection-retrieval times from days to minutes.

Figure 1: Film still of archive move into the new Sammy Ofer Wing stores

Responding to this opportunity—and building on ten years of sustained digitization—the Museum developed a physical space and new website to showcase its vast collection and invite visitors to use objects in a more active way.;.

1. Introduction to projects

Collection website

The Research Information Network report (2008) found that “what researchers need above all is online access to the records in museum and collection databases to be provided as quickly as possible, whatever the perceived imperfections or gaps in the records.”

While we were determined to produce a beautiful new website that led with large collection images (http://rmg.co.uk/collections), we also resolved to make as many records as possible available to the public. By redefining the mandatory fields to include just object ID, description, and credit line, we were able to increase the number of publicly available records from 80,000 to over 400,000.

The redesigned website promotes a more active engagement: Users can tag or share objects, save searches, create their own groupings, download images, order prints, or request an item to view in the library. The website is also linked to external sites and services such as print on demand (http://prints.rmg.co.uk/), the library and archive retrieval system (https://archiveandlibrary.rmg.co.uk/aeon/), WorldCat (http://www.worldcat.org/), and social media networks.

Further to this, members of the public are invited to contribute their own knowledge to the catalogue, and verified contributions are credited on the object records.

Figure 2: Screenshot of collection website homepage

The Museum is already a sector leader in contributions to sharing initiatives, such as The Commons on Flickr (http://www.flickr.com/photos/nationalmaritimemuseum/), Wikimedia UK (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wikipedia:GLAM/NMM), Europeana (http://www.europeana.eu/portal), and the BBC’s Your Paintings (http://www.bbc.co.uk/arts/yourpaintings/), but we wanted to encourage self-facilitated reuse of our data. The Museum therefore changed the end-user license to Creative Commons (CC0 for data and CC3 for images), exposed the underlying Application Programming Interface (API), and created a SPARQL endpoint. The API enables developers to create applications or interactives using the Museum’s collection data. The SPARQL endpoint makes it easier for developers to query multiple data-sets, for example, to combine museum collections.

Launched in July 2011, the API delivers content to the Museum’s own on-gallery services and interactives, and is already being used by sector-wide aggregators, such as Culture Grid (http://www.culturegrid.org.uk/), Europeana, The Digital Public Space (a cultural sector and BBC Archive prototype), and the Public Catalogue Foundation (http://www.thepcf.org.uk/).

Taken together, these changes reposition our collection website as a dynamic provider and receiver of information.

Compass Lounge

The Compass Lounge, designed with Kin (http://kin-design.com), is a comfortable space that invites visitors to take their time exploring and discussing the collection. It comprises three “interactives” that creatively display over 5,000 digital reproductions in order to expose the connections between objects.

The space is wallpapered with large graphics that mix maps and charts from our archive with modern references, such as the distinctive marker pins from Google Maps. This background is overlaid with a mixed-media display that is to be updated biannually through a process of co-curation with selected community groups.

The display is made up of eight large frames for print material and nine small screens for digital images and video.

Figure 3: View of the Compass Lounge

Co-curated display

For the opening in 2011, there was a selection of historic photographs displayed as large prints, each labelled with a call-to-action to contribute to the Museum’s records via the collection website:

Help describe this photograph: add a tag online

rmg.co.uk/collections

Accompanying small screens displayed selections assembled by Museum staff and encouraged visitors to create their own groupings:

Create your own collection online

rmg.co.uk/collections

Horizon installation

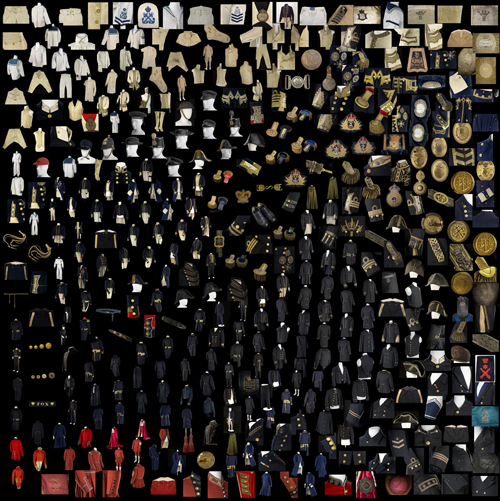

The Horizon is a multi-screen visualisation of the Museum’s collection. Over 4,000 images from five collections—ship models, oil paintings, flags, uniforms, and coins/medals—are grouped by visual similarity. This aesthetic arrangement began by using “computer vision” software from the University of Dundee to extract and compare colour and texture information. Computer vision aims to equip computers and robots with the ability to understand images. Professor Stephen McKenna, chair of computer vision at the University of Dundee, describes it as a “means [of] enabling machines to recognise people and actions in videos… or retrieve images similar to example ones from large repositories” (University of Dundee, 2011).

Fig 4: 2D layout of the National Maritime Museum collection of uniforms. Image by University of Dundee School of Computing.

This unique configuration of objects, produced on a two-dimensional (2D) plane, was then placed within a 3D environment, creating a stream of images that the viewer explores by rolling an oversize trackball. The objects are presented “fit to screen” across the five 40*inch screens, rather than being accessed via a thumbnail, and are shown without text descriptions. The images are all presented at the same scale so each object has equal status.

Figure 5: Horizon installation. Image by Kin.

Plan Chest installation

The Plan Chest is a physical embodiment of the Museum’s collection website. Wooden drawers are pulled out to reveal large touchscreens, each showing high-resolution images of the most popular objects—that is, the objects that have been the most viewed, shared, collected, or tagged. In doing so, the Plan Chest showcases the collection in use.

Figure 6: Plan Chest installation. Image by Kin.

A linked light-emitting-diode display shows the relevant accession number, highlighting this unique key to all of the Museum’s information about an object.

Compass card

Every visitor to the Museum is given their own Compass card to reveal the hidden connections between people and the objects in the collection, in the form of beautifully packaged stories.

Figure 7: Compass Card explanatory film (http://vimeo.com/36045405)

The visitor begins his or her journey either by visiting the Compass Lounge or by collecting selected objects in galleries.

The card is stamped at distinctive Compass units that accompany selected objects; this activity is recorded digitally via the unique barcode and physically through an embossed symbol. Once the visitor has collected an object, he or she returns to the Compass Lounge to unlock the corresponding stories or visits the website at home to do the same.

Each story takes the visitor on a journey through the collection from the starting object to connected people, objects, and archive material. This content is presented as stories with dramatic titles such as The Intrepid Amateurs, The Legends of Hull, and The Hunt for the Lost Explorer.

As soon as visitors register their cards, they’re sent a free, personalised e-book, which is determined by the objects they collected during their visit to the Museum. This e-book is a book from the Museum’s Caird Library collection that also happens to have been digitized by Project Gutenberg (http://www.gutenberg.org/).

Figure 8: A Compass e-book, by Kin

The symbols on the cover are the same as the ones visitors happened to collect on their card during their visit. The email containing the e-book also has an invitation to visit the Caird Library in order to view the “real thing.” Visitors simply use the “request an item to view” feature of the collection website to plan their visit. In so doing, the visitor has taken a journey from a selected object in a gallery to a hands-on experience with relatively hidden archival material in the library.

Figure 9: Bloggers’ preview of new Caird Library research and reading room, by Dianne Tanner

2. Design and interpretation

The design of the Compass Lounge was led by five interpretative principles:

- A playful fusion of the physical and digital can stimulate curiosity;

- Objects with limited or no imposed interpretation can provoke extended reflection and conversation;

- “Peopling the collection” makes archives more accessible;

- Visitors need to understand that the collection is there for them to use—and how to go about it;

- An object can be a start, rather than end, point.

Physical-digital interplay

There is a constant interplay between the physical and the digital in the Compass Lounge and a deliberate playfulness in the transitions between the two states. The furniture objects themselves stimulate curiosity by introducing digital experiences in novel ways.

Each furniture object suggests a different kind of interaction: a seated, in-depth experience with the Compass; a playful exploration of the Horizon; and hidden things to uncover in the Plan Chest.

For example, the over-sized drawers of the Plan Chest reference the physical structure of the archive. By placing digital reproductions within this evocative furniture, we invite visitors to discover things in new ways.

There is a carefully crafted balance of things the visitors expect and things they don’t. Digital technology allows us to do this in really interesting ways. The Compass units contain an embosser so cards are stamped with tactile symbols as stories are collected. The units have no obvious digital expression—despite their internal use of barcode technology—so their memory of visitor actions is more delightful.

Visualising the collection

The view of the collection offered by the Horizon transcends museum classifications, allowing thousands of objects to be seen without imposed interpretation. It was a deliberate challenge to the conventional overview offered on a collection website, where text predominates and objects are visually represented by thumbnails.

In the Horizon, the images are presented at the same scale so each object has equal status. In this view, Nelson’s Trafalgar uniform demands no more attention than any other blue frock coat.

Representing collections in this way exposes patterns. As information design specialist Edward R. Tufte says in Visual Explanations (2002), “Multiple images reveal repetition and change, pattern and surprise – the defining elements in the idea of information... Multiples amplify, intensify, and reinforce the meaning of images.”

Looking at the uniforms, a visitor may see swathes of the particular blue that inspired the naming of the colour navy blue. Their eye may also be drawn to part of the collection that is often overlooked, the Marines’ uniforms, in a small but noticeably red band. Ordering the ship models by texture exposes technological development, seen in the clusters of sails, oars, and masts. Looking through the layers of flags, it becomes apparent that their restricted colour palette was honed to improve visibility at sea.

This form of display can bring the viewer closer to individual objects. The coins are shown larger than their real size, which reveals details that might be missed when looking at the original object.

In his Canvas prototype (http://timwray.net/2011/12/canvas), museum informatics student Tim Wray uses similar clustering techniques to a very different end. Wray was inspired by Tufte’s (2002) criticism of the absence of scale in reproductions:

Although the physical scope of a work of art is not always a relevant variable, for some works – Lichtenstein’s mural, Monet’s water lilies… colossal statues of David or the People’s Heroic Leader, posters, delicate and precious miniatures, postage stamps, typography – their size is surely an expressive factor. How then can tiny, irregularly scaled reproductions tell us about measure, magnitude, presence, absolute or relative size?

Wray developed Canvas both to restore comparative scale to a museum catalogue and present looser connections between objects: “Clusters of objects are arranged, laid out and scaled according to their real dimensions... and join other, branching paths that diverge and form new pathways” (Wray, 2012).

Where the Horizon installation and Canvas prototype are similar is that they both invite the viewer to be an active interpreter of the collection, making contrasts and comparisons. In describing the effect of the sequential presentation of images, Tufte (2002) observes that “the perceiving mind itself actively works to detect and indeed generate links, clusters, and matches among assorted visual elements.”

Peopling the collection

The Compass Lounge aims to move visitors by telling stories about people. The Compass stories are micro-biographies of both “great men” and “silent voices” drawn from the Museum’s archives. They range from the heroic figure of Admiral Nelson to the relatively unknown George William Smith, a Hull fisherman who was killed at sea and whose death nearly triggered a war between Britain and Russia.

Similarly, the adjacent orientation gallery, Voyagers, displays over 200 objects, organised according to the emotions they symbolise (i.e., anticipation, love, sadness, aggression, pride, joy) and interpreted through individual stories, such as:

- A letter from Horatio Nelson to Lady Emma Hamilton, written from Victory in 1803. In this letter, Nelson tells Emma she will be ‘'my own Duchess of Bronte.”

- A teddy bear mascot called Humphrey belonging to Tracy Edwards and carried on the racing-yacht Maiden during the 1989–90 Whitbread Round the World Yacht Race. The toy has lost its legs, its right arm is partially missing, and it has no eyes—the result of falling during a storm into a bilge pump from which it was retrieved some weeks later.

This is further developed through a series of video portraits of people from all over the world—coastguards, émigrés, naval officers, schoolchildren—each telling his or her own story of the sea.

The first co-curated display in the Compass Lounge was conceived by the Museum’s Youth Advisory Group and opened in February 2012. For this display, the Youth Advisory Group selected two people that they felt were under-represented in the Museum’s Traders gallery—Jamsetjee Bomanjee Wadia (1756–1821) and Sake Deen Mohamed (1759–1851)—and worked with photographer Maisie Maud Broadhead (http://www.maisiebroadhead.com/) to reenact imagined scenes from the lives of these characters. The resulting photographs use contemporary references to suggest the enduring relevance of trade between Britain and India. The accompanying small screens show related objects from the Museum’s collection researched by the group.

Figure 10: Photograph by National Maritime Museum Youth Advisory Group and Maisie Maud Broadhead

Many other museums are actively uncovering “people stories” and using digital technology to do so: crowd-sourcing and computer vision techniques have proved particularly effective.

The London Lives website (http://www.londonlives.org) makes available over 240,000 digitized manuscript and printed pages, providing access to over 3.35 million name instances, many of them for the otherwise invisible classes of the eighteenth century. Users are invited to collect and link together records relating to the same individual, and to compile biographies of the best-documented individuals. According to Heller (2012), “London Lives allows us to begin to trace individual life trajectories of the labouring poor and of Londoners caught up in the criminal justice system. It is now possible in a matter of days or weeks to assemble evidence related to single individuals that would previously have taken years or decades to amass.”

In Faces of the First World War (http://www.1914.org/faces/), the Imperial War Museum shared 100 portraits on Flickr, inviting the public to help identify the men who fought for Britain and the Commonwealth during the First World War. This is just the first phase of an ambitious project to uncover millions of life stories through volunteer annotations of letters, diaries, and photographs.

The real face of white Australia (http://invisibleaustralians.org/faces/) is an experimental prototype by digital humanist Tim Sherratt. Sherratt used computer vision to find and extract photographs of people from the records of the White Australia Policy, held by the National Archives of Australia. Having identified 7,247 photographs, Sherratt then presented them as a visual interface to the records, “not as the remnants of bureaucratic processes, but as windows onto the lives of people. This is also a finding aid... that brings the people to the front” (Sherratt, 2011).

Showing the collection in use

Visitors need to understand that the collection is there for them to use—and how to go about it. The Compass Lounge brings more of the Museum’s collection to the attention of the public by using a starting object or collection to highlight how each object is part of a larger story, or has connections to other objects and archival material. At each point of his or her experience, the visitor is made aware of the collection website and how he or she can interact with it.

Every object on display in the Museum—whether a ship model, map, or photograph has its own unique reference, known as an accession number. This number is used to identify, locate, and store information about an object. The panel interpreting the Plan Chest explains how to read the number, and how to use it to access everything the Museum knows about an object:

How to read the number

Most of the Museum’s accession numbers start with a three-letter code. In some cases, this reveals the type of collection the object belongs to: e.g., SCU is for sculptures, GLB for globes, and AST for astronomical instruments.

The four numbers following the code uniquely identify a particular object.

Sometimes you will see that an accession number has a decimal point and another number. This shows that the item is made of several parts, such as a sword (WPN1000) and the sword’s scabbard (WPN1000.1). This helps to keep related objects together.

We are now developing an accompanying mobile website, optimised for quick accession-number searches.

The Plan Chest also visualises public use of the collection: the objects that appear in the drawers are determined by what is being viewed, tagged, and shared online. In the future, we hope to find ways to similarly represent research activity and creative reuse of the collection.

For example, every object on the Powerhouse Museum’s collection website (http://www.powerhousemuseum.com/collection/) includes Wikipedia citation code, which both promotes attribution and serves as a call to action. Brooklyn Museum takes this further by actively tracking and reporting on the uses that Wikipedia contributors have made of the thousands of images the museum has uploaded to Wikimedia Commons: Where in the Wikiverse is the Brooklyn Museum? (http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/opencollection/labs/whereinthewiki.php).

Object as starting point

Some museums are moving towards having dense displays of objects, arranged pretty much as they would be in a back-of-house store, and limited, if any, fixed interpretation.

Brooklyn Museum has a 5,000-square-foot Visible Storage Study Center (http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/luce/). Whereas only about 350 works are on view in the adjacent exhibition, the visible storage facility gives open access to some 2,000 of the many thousands of objects held in storage, which are available for viewing and research by the public. There is an accompanying leaflet that explains how the accession number can be used to access more information about the objects on display.

Similarly, the No. 1 Smithery (http://www.rmg.co.uk/no-1-smithery/) is a collections research area founded by the National Maritime Museum, in collaboration with the Chatham Historic Dockyard Trust and the Imperial War Museum. Here, more than 3,000 ship models are available to view, by appointment. To facilitate this experience, the entire ship model collection was digitized and made available online.

For its temporary display of 650 red and white quilts from the collection of Joanne Rose, the American Folk Art Museum created a spectacular sculptural installation free of any labels: Infinite Variety (http://www.folkartmuseum.org/infinitevariety). Visitors who wanted more interpretation could download a free app.

Similarly, for an exhibition of women pop artists, Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists (http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/exhibitions/seductive_subversion/wiki/), Brooklyn Museum dispensed with traditional interpretative labels. Instead, the exhibition curator edited the twenty-five Wikipedia articles relating to the artists and showed these pages on iPads at each end of the gallery. In this way, the paintings are an entry point to all knowledge about the artists—not just that held by the museum—and invited visitors to make their own contribution.

3. Evaluation

A formal evaluation of the Compass Lounge was carried out in November–December 2011 to discover what questions and conversations are provoked by a display of objects with little or no interpretation; to understand whether “peopling the collection” really makes archives more accessible; and to establish whether visitors understand that the collection is there for them to use, and how to go about it.

Observations and interviews

The evaluation took the form of observations and interviews both in the Compass Lounge and in two galleries that include Compass units: Voyagers and Traders. The aim was to observe visitors, especially inter-generational groups, as they dwelt in the space and/or used the three interactives.

A total of eighty-seven visitors were observed, and twenty interviews were carried out with visitors over thirteen years of age. For sixteen interviewees, it was their first time in the Compass Lounge. Four interviewees had been before—one of them many times.

A further twenty-five visitors were interviewed at the exits of the Voyagers and Traders galleries. Gallery interviewees were asked whether they had a Compass card; how they discovered it; whether they had collected stories from the gallery or other galleries; if they intended to collect other stories; and what they expected to get when they took their card to the Compass Lounge or accessed the information gathered at home.

Key findings

The Compass Lounge inspires conversation

One of the primary aims of the Compass Lounge was to inspire collection-related dialogue between visitors. We found that visitors used the Compass card together, discussed the mechanics of how it worked, reacted positively to the stories collected, and talked about following up at home.

Interactions at the Plan Chest included selecting objects on the screens, reading the short descriptions, looking closely at details of the objects, and discussing with others what was found. For example, a child looking at the Plan Chest was joined by his grandfather:

“Oh wow, look at that, do you know what that was used for?” [The child’s grandfather then gave further explanation of spitfires. They returned a few minutes later:] “I think I've found a gunship.”

Inter-generational groups were particularly attracted to the Horizon. Families were observed taking turns and giving each other instructions: “forward, back” and “up, down.” There were involved discussions of the categories, objects, and details.

Children liked the soundscape and being able to roll the ball around to see images:

“Look dad, wow look what I have found… I’m fast-forwarding… Look at these flags… It’s fun going backwards.”

Other visitors liked the controls, the variety of images and being able to zoom in to see details:

“I would stay in it all day... It was great to interact with paintings, to see the detail, see texture. You could see the overall impression of trends, styles evolving.”

Groups also made up stories of their own around ships and battles and talked about people featured in the images. For example, a five-year-old boy asked his mother, “Where’s Jack Sparrow?”

Another child said:

“I liked the coins. I would like a big boat in this space. I saw a flag but it was only blue and red (and had) no white on it—so not the English flag.”

Visitors are made aware of how to access the wider collection

Over half of the interviewees who had looked at the Plan Chest or mixed-media display said that they would use the collection website after their visit. A slightly smaller proportion understood that each object had an accession number and that this number could be used to find out more about a particular object. One in five interviewees expressed an interest in visiting the new research and reading room in the Caird Library to see the Museum’s prints, letters, and charts.

A small number of visitors requested additional—but still limited—information; for example: “A way to pull up captions on the Horizon. Maybe with a time stamp, a quick idea of the artist or era.”

Visitors do not spend as long in the lounge as anticipated

The Compass Lounge was designed to be a space where visitors felt comfortable “hanging out,” having a rest, reading, or using their own devices. Flexible furniture, free public wifi, and accessible power boards were installed for this purpose. However, while visitors are engaging with the Horizon, Plan Chest, and Compass Card, the space is not being used for long periods as a “lounge.”

While the majority of visitors take advantage of the seating, most do not use their own technology, and only a quarter of visitors rest in the Compass Lounge for more than ten minutes. However, most visitors do describe the lounge as comfortable, and some parents use the Horizon to take some time out. For example, one father sat on the seats reading the free Greenwich paper while his son explored the Horizon.

|

Time spent |

Number of visitors |

|

up to 5 minutes |

41 |

|

6–10 minutes |

24 |

|

11–15 minutes |

7 |

|

16–20 minutes |

6 |

|

21 minutes |

4 |

Table 1: Time spent in the Compass Lounge

Web metrics

In the six months since launching the new collection website and Compass card, there have been:

- Over 5,000 registered users of the card.

- Four referrals per day to the print-on-demand website.

- 180 records updated in response to contributions from the public; for example:

Dear Madam/Sir, This is not “Konia” inscribed on the plan. This is “Копия,” which means “Copy” in English. Inscriptions under Body plan are “Plan of a seagoing vessel” with principal dimensions.

(http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/84971.html)

Fred Bell was a guard on the railways in Hull. At the time of this portrait he was working as a docks manager or deputy docks manager in Hull. He was also a member of the local home guard, guarding the docks in Hull. Fred Bell was a decorated soldier from the First World War.

(http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/14019.html)

The model of the Sirron engine has been dated too early. This type of engine did not appear until 1942 for the development prototype and 1944 for the first production engine. It is believed that the model you have was made for display at the ‘Festival of Britain’. I trust this is helpful. I have no idea where to search for specific display area at the festival but I will let you know if I get anywhere.

(http://collections.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/68075.html)

4. Next steps

Planned improvements

Gallery dispensers for the cards

Staff do not always distribute Compass cards at the entrance to the Museum, and cards are most likely to be requested by visitors when they’re in a gallery with Compass objects. Introductory panels and dispensers, using the distinctive graphic language of the Compass Lounge, are therefore being integrated within the relevant galleries. (The Compass card is already featured in the wayfinding system and distributed at visitor information points.)

Continued rollout of the system

The Museum has a master plan for the next ten years that covers the redevelopment of all its permanent galleries. As such, the Compass card will eventually feature in every permanent gallery. Further card readers will be introduced to other public areas so that visitors are able to register and view stories without necessarily having to return to the Compass Lounge.

Volunteer hosts in the lounge

Shortly after the Compass Lounge opened, the Museum assigned volunteers to host the space, helping with the technology, directing visitors to the relevant galleries, and assisting with the public wifi. We’re keen to develop this role beyond the practical help that is already offered.

The Compass Lounge is deliberately light on interpretation, and while this prompts visitors to look closely at the objects and develop their own thoughts, it also leads to questions. We would like to equip our volunteers with the resources that would help them answer questions about the collection.

Figure 11: Steve, a Compass Lounge volunteer

Children’s card

Our evaluation has shown that the Compass system is incredibly popular with children. It was designed for family groups, but observation has shown that young children take the lead: They are given the card to collect objects and return to look at the content with family members. We will therefore add a layer of content created specifically for children aged seven to eleven. The starting objects will remain the same, but children will discover stories that are more meaningful to them.

Mobile interpretation platform

We’ve almost completed development of a new system that reinterprets galleries on the fly for specific audiences, such as schools and family groups. An augmented reality layer will be delivered via an Android tablet, shared within small groups of two to three people, to promote a social experience. The tablet works like a porthole to the galleries, with a live video feed acting as the background to the interface.

Figure 12: Screenshot from the mobile learning platform (in development)

The tablet uses location tracking and computer vision to provide three different kinds of interactions:

- Discovery: the tablet automatically presents new objects and media in real time, responding to visitors’ movements

- Enquiry: visitors can use the tablet to request more information or media relating to a site of interest

- Manipulation: visitors create and/or control digital objects.

To enable real-time tracking of visitors’ movement in Museum spaces, we are using a mix of wifi positioning and an ultra-wideband radio tracking system. To identify particular objects, or more granular locations, we’re using a system for intelligent image recognition, provided by Cortexia (http://www.cortexica.com/). In short, this works by matching visitors’ photographs to a predefined database of images.

5. Conclusion

At the National Maritime Museum, we’re designing object-based museum experiences that seamlessly traverse physical spaces and digital platforms. We contend that museums could reveal more of their collections by producing dense displays of objects with limited fixed interpretation but hooks into deep digital services and invitations to participate, especially as computer vision brings the possibility to refine this interaction and make it more magical. The object can then act as a “service avatar”: all of the evocative power of an object, used to access digital experiences.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to our colleagues Lucinda Blaser, Henry Holland, Stephen Warwick, and Jane Findlay. Thanks also to Kin (http://kin-design.com), the lead designers of the Compass Lounge—especially Matt Wade and Panja Göbel. Our evaluation study was carried out by Nicky Boyd (http://www.nickyboyd.co.uk).

References

Heller, B. (2012). Review of London Lives 1690–1800—Crime, Poverty and Social Policy in the Metropolis (review no. 1001). Consulted January 29, 2012. Available at: http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews/review/1001

Research Information Network. (2008). Discovering physical objects: Meeting researchers' needs. Consulted January 29, 2012. Available at: www.museumsassociation.org/download?id=17925

Sherratt, T. (2011). It’s all about the stuff: Collections, interfaces, power and people. Consulted January 29, 2012. Available at: http://discontents.com.au/words/conference-papers/it%E2%80%99s-all-about-the-stuff-collections-interfaces-power-and-people

Tufte, E.R. (2002). Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative. Cheshire, Connecticut: Graphics Press.

University of Dundee. (2011). “University to host computer vision conference.” Consulted January 29, 2012. Available at: http://www.dundee.ac.uk/pressreleases/2011/august11/computingconference.htm

Wray, T. (2012). Canvas. Consulted January 29, 2012. Available at: http://timwray.net/2011/12/canvas/ Dec 2011