1. Introduction

'Imagine you can experience the Colosseum back in its original state, see the audience sitting on the benches and hear the lions roar.'

In the 21st century the media are going ambient. TV, as Anna McCarthy pointed out in Ambient Television(2001), started this great escape from domesticity via the manifold urban screens and the endless flat screens in shops and public transportation. Currently the Internet is going through a similar phase as GPS technology and our mobile devices offer via the digital highway a move from the purely virtual domain to the 'real' world. We can collect our data everywhere we desire, and thus at any given moment transform the world around us into a sort of media hybrid, or 'augmented reality'.

Museums, continuously looking for ways their artifacts can be layered with stories, combined with half a century of experience with handheld media and a permanent need to reach new visitors outside of the white cube, have been on the forefront of experimenting with the hottest mobile technologies. In the past year, the innovative forms of augmented reality (AR) appearing on smartphones have proven to be exciting playgrounds for curators and museum educators.

These AR tools offer users the possibility to deploy their phones as pocket-sized screens through which surrounding spaces become the stage for endless extra layers. This visual collision of the real and the virtual will hopefully culminate in what we have seen in movies like Minority Report (2002), where Tom Cruise navigates with his body through 3D data: a seamless interface of the body, the virtual and the real that might in the future be actualized.

We can, of course, already envision the potential of such technologies for museums: a small shard of pottery will be augmented by a complete and beautiful vase, while the skeleton of a dinosaur will be layered with muscle, tissue and skin. We can indeed imagine seeing the audience sitting on the benches in the Colosseum, even hear the lions roar, as Layar, a Dutch AR provider, promises us.

Currently, however, AR technology is still a kind of experimental notion, as yet lacking the total immersion for which we yearn. Moreover, its mediation through a tiny handheld screen poses several challenges to augmented storytelling. What, then, does this contemporary form of AR have to offer the museum? What kind of museum experience does it generate?

2. The project

This paper will answer these questions by taking the ARtours project of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam as a central case study. This particular augmented reality project was initiated by the Stedelijk, in collaboration with design bureau Fabrique, in autumn 2009 and runs to the end of 2011. It is generously funded by the Dutch Ministry of Culture (Innovatie Cultuuruitingen/agentschap.nl).

One of the major reasons for turning to augmented reality (AR) is that the Stedelijk Museum is awaiting its grand re-opening. It seems, therefore, the appropriate time to explore the potential of new media technology and to find innovative ways in which the museum's collection of modern and contemporary art and design (90.000 objects) can be presented, in addition to reexamining how the stories and interpretations that surround these objects can be shared.

Utilizing AR on smartphones seemed particularly interesting, as the Stedelijk Museum, for years homeless due to a renovation of its original premises and the construction of a new wing, has been drifting from one location to another in the city of Amsterdam. The new dialogues this generated with the urban realm, the people in the street and various Amsterdam cultural institutions proved to be very powerful and inspiring – and essential to continue. Even now, while the museum has (temporarily) returned to its old habitat, the urge is strong to keep connecting the collection and its stories to the outside world.

AR appeared to be the perfect medium for this purpose, as it is now mainly used outdoors because of its GPS requirements. Several museums around the world immediately saw the potential of this new medium. As the AR applications of the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, Australia, and the Street App of the London Museum illustrate very well, the technology allows cultural institutions to thrust their digitized artworks out of the database into the streets. Both tours are based on the principle of tagging historical street view photographs and paintings from the museum's collections with the place they were produced and/or depicted many years ago. The viewer is thus offered a visual blend of the 'now' and the 'then', which of course leads to all sorts of fascinating narratives about urban and social changes.

The Netherlands Architecture Institute (NAi) has added further layers to this model in its unequaled UAR application. With it users can point their smartphones at the cityscape around them and find not only previous architectural models but also planned architecture that was never developed on a site, as well as architecture that is not yet built but will be in the future. Especially in Rotterdam, NAi's pilot and anchor city, this proved to be a perfect form of multi-time layering, as the city has undergone so many changes due to the Second World War and contemporary growth.

Fig 1: UAR, NAi's AR architecture application

Fig 1: UAR, NAi's AR architecture application

The ARtours project of the Stedelijk Museum discussed in this paper also explores this kind of augmented reality storytelling based on using the collection to bring several time frames together in the urban realm. However, for a museum of modern art there is much more to explore. What about the hacking of spaces for new exhibitions? Can we turn the visitors into AR curators/narrators? What can artists accomplish with this new medium? What happens once we bring AR inside the museum building?

These questions and many more are fuel for the ARtours project, which consists of several smaller and larger projects that test all possible forms of the (interactive) augmented reality platform, both inside and outside the museum, leading up to the building of an open source content management system for museum ARtours.

What follows is a description of what we have learned up to this point, concluding with a critical evaluation of current technology and future AR developments.

3. Learning from ARtours

Getting started

From the outset of the ARtours project, one of the main goals was to explore and investigate the possibilities of AR and its impact on the user experience. After funding was raised, the project kicked off in January 2010 - a period in which the technique incorporated in the augmented reality browser Layar had existed for no more than half a year. At the time, we expected development in the features of this particular AR browser but also the emergence of other initiatives in the coming years. Primarily for this reason, we experimented with small projects, focusing on different aspects of AR and its impact on the user experience, before developing the project's main product.

In the first year we experimented with three small projects and made an initial start on the main product. Results from each project were included in the next as lessons learned.

Me at the Museum Square

Soon it was time to shift our focus from research and ideas to conceptualizing these and start building prototypes. After all: the proof of the pudding is in eating it.

The first project was carried out in collaboration with students of the University of Applied Science in Amsterdam. The briefing for the students was not detailed and could be interpreted in many different ways, as was intentional. In this early stage we wanted to explore the different angles of the use of AR in relation to art. In short, the assignment was to develop an AR application with the use of the Layar technique that had something to do with art (optionally the collection of the Stedelijk Museum) and that should take place outside (i.e. not within the museum).

The concept created for this project was a virtual 3D-artwork exhibition which was located adjacent to the museum's premises at Museum Square. Students of various Dutch art academies were approached to create 3D artworks for this special exhibition.

The underlying rationale behind this concept was threefold. First, it seemed difficult to use the collection of the Stedelijk because of the lack of curatorial knowledge in the student group. Second, the assignment was to explore in the broadest way possible the technique of Layar; therefore the students chose to use 3D objects. The third reason was the possibility of holding an event when the exhibition launched. In this way both utilization and experience of the application could easily be observed.

Questions to be answered in this project were as follows:

- What are the possibilities of using 3D objects in Layar (with a focus on technology?

- What can artists create, taking into account the limitations of the technique?

- What will it bring to the user experience?

The first step in this project was to gather a comprehensive overview of the opportunities and limitations of the technique, the augmented reality browser. Tests were conducted on the iPhone 3GS and the Motorola Milestone.

Next, the GPS accuracy and the performance of 3D objects were tested. Outcomes of the tests were incorporated in the briefing for the art students (for detailed conclusions, see http://ikophetmuseumplein.nl/info.php).

Curatorial staff of the Stedelijk then viewed and rated the artworks of the students. From all the entries, six works were selected to be realized in 3D.

On May 28, 2010, the exhibition was launched at Museum Square. The first observations during the launch were most valuable.

Fig 2: Museum Square, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. On the left the Stedelijk Museum building is visible

Fig 2: Museum Square, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. On the left the Stedelijk Museum building is visible

The event took place in the late afternoon on a sunny day. Due to the late hour, the majority of phone batteries belonging to the visitors were no longer fully charged. After 45 minutes, most devices were out of power. Because of the sun and its placement in the sky, it was difficult to see what was on the device screens. The students anticipated this and distributed sunshades. The sun's trajectory caused further inconvenience, as visitors were forced to walk around while holding their mobile devices pointing at the sky. A map and the assistance of museum attendants were necessary to guide visitors to the different artworks. Although thoroughly tested, the GPS accuracy was sometimes poor, causing objects to appear in the wrong place.

Fig 3: Map of art object on the Museum Square

Fig 3: Map of art object on the Museum Square

One of the artworks combined a 3D object with sound. In some cases, sound was not audible or didn't have the right timing. The Layar technique at that time was still experimenting with sound integration. Currently these techniques are much improved.

An unexpected observation was the way the application stimulated interaction among visitors. Not every visitor had a smartphone with the Layar application. Whereas we expected visitors would walk around individually, groups formed and together they walked around Museum Square to view the artworks. Even passers-by became interested and asked whether they could watch what was happening.

Fig 4: Looking together at the artworks, with sunshades

Fig 4: Looking together at the artworks, with sunshades

ARtotheque (Kunstuitleen)

When the music festival 'A Campingflight to Lowlands Paradise' asked the Stedelijk Museum to participate in its diverse side program, the ARtours project answered the call.

Lowlands, as it is popularly called, is a three-day festival in the Netherlands with a focus on music (from rock to dance, pop to punk). It has a strong side program consisting of public interventions by actors, art installations, debates, stand-up comedians, film and transmedia projects. In short, it was a perfect environment for experimentation with the second project.

With a small team comprised of curators of the museum, programmers and (digital) artists, we developed a concept called ARtotheque. The idea is simple: an ARtotheque functions similarly to a public art library. It's a place where one can borrow art for a certain price and a certain period of time. The Stedelijk Museum holds thousands of artworks in its collection, so why not lend them to the general public?

Augmented reality posed the solution. Instead of the real thing, a visitor to the Lowlands festival could borrow a replica in AR. In order to make it an interesting user experience, the visitor could download the artwork to his/her smartphone and position it anywhere on the festival premises.

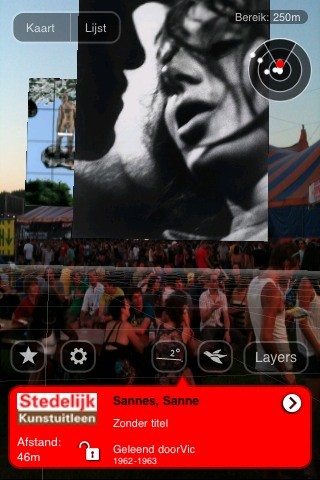

Fig 5: Stedelijk Kunstuitleen: Sanne Sannes

Fig 5: Stedelijk Kunstuitleen: Sanne Sannes

We assembled a booth on the festival grounds for use as a store front, through which we connected with the audience. From a reasonable distance, anyone could see that the Stedelijk Museum was present at Lowlands, and hundreds of visitors passed by our window. Many with an iPhone or an Android smartphone stopped and tried out the ARtotheque.

Participation was relatively simple: the visitor could choose an artwork from a selection of 160 masterpieces, all printed on A4 cards, scan the QR code on the card and thus activate the 'Kunstuitleen' (art loan) layer on the Layar platform. The last step was to choose a position for the artwork, hang it and share it with all other works in the public 'Kunstuitleen' layer.

In terms of attention, visibility and public reception, the ARtotheque was a huge success. The project was all over the news and got quoted in various blogs. The user interface and experience were adequate for this special event.

On the downside, we ascertained that a good AR experience relies heavily on reliable connectivity. The moment 60,000 music fans entered the festival, all calling and texting each other, 3G reception no longer functioned.

We had to set up an (unauthorized) Wi-Fi-spot to make at least some experience possible. In the end, 45 artworks were borrowed.

We presumed to reach out to the young and restless, but found that they either didn't own a smartphone or were afraid their battery would run out too quickly. Most art was lent to visitors in their thirties or forties.

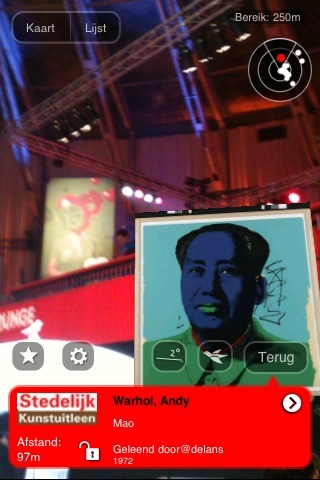

The concept of the ARtotheque was also used at the PICNIC festival. PICNIC is about innovative ideas for business and society. It is an annual three-day festival that blurs the lines separating creativity, science, technology and business to explore new solutions in the spirit of co-creation.

The ARtotheque @ PICNIC gave us an opportunity to test our application in different circumstances.

Instead of in the open air, we were positioned in a large dome. We had Wi-Fi connection throughout the festival grounds and no shortage of electricity sockets. Furthermore, some 90% of the visitors owned a smartphone. This resulted in a significant rise of borrowed work; nearly 130 artworks changed hands. It also had a second benefit: PICNIC connected us with a peer network of innovators. On the downside, working under a steel dome made GPS positioning difficult and blurred some of the artworks on display.

Fig 7: Stedelijk Kunstuitleen: Andy Warhol

Fig 7: Stedelijk Kunstuitleen: Andy Warhol

Stedelijk AR(t): Jan Rothuizen

It's one thing to open up your collection in AR, but quite another to curate an artist who will create a work using AR as a canvas. As we are striving towards the creation of a platform that enables both, this third project is a step in that direction.

The temporary opening of the museum's renovated gallery space (constructed in 1895), awaiting completion when our new wing will be attached to the original space, presented us with an opportunity to stage a project using AR possibilities indoors.

Together with our curators, we invited Jan Rothuizen to come up with ideas for an exhibition, solely viewable in augmented reality.

Jan Rothuizen (b. 1968) is a Dutch artist who works primarily with pen, ink and paper. He draws sociographs, maps, and situations, which he enriches with written thoughts and observations. As a child, he grew up next door to the Stedelijk Museum. With his family he visited the museum on a regular basis in early childhood, and thus received an early education in art. As a graffiti youngster, he assisted Keith Haring during the artist's residency at the Stedelijk Museum.

We introduced the medium to Rothuizen and discussed the possibilities and constraints of working with AR on a mobile device. He agreed, and we commissioned the work.

As Rothuizen started to conceptualize his ideas, we connected him with our technical and design partners, TABworldmedia and Fabrique. We decided to use the Layar platform to publish Rothuizen's artworks.

In the resulting work, Rothuizen's drawings are virtually appended to the spaces of the building to which they refer. The result is a layering of the museum with virtual information, bringing the objective outer world of material spaces into collision with the subjective inner world of conceptual memories and storytelling: a mapping of the museum inside the museum. In order to experience this as a visitor, you need to download the Layar AR-browser and look up the 'Stedelijk AR(t): Jan Rothuizen' layer.

Fig 9: Stedelijk Museum AR(t): Jan Rothuizen

Fig 9: Stedelijk Museum AR(t): Jan Rothuizen

We launched the application at the 'Play it!' evening, a night in the museum's auditorium dedicated to augmented reality and urban games in an artistic context. What we found is that visitors tend to look together at the AR artworks instead of making it an individual experience. Perhaps this is because fewer people have iPhones or Android smartphones. It may well just be that art is still consumed at its best when you can share it with the people around you.

The 'Stedelijk AR(t): Jan Rothuizen' application is a step in the right direction. We learned what works and what doesn't when it comes to enjoying the artwork through your mobile telephone. Working under a roof makes it hard for the application to get the GPS positioning right. We discovered that on the top floor of our building the reception is just good enough to work with AR. By installing a Wi-Fi network, we ensured connectivity. The Wi-Fi, in conjunction with the internal compass of the telephone, gives reasonable positioning feedback to the application. We might in the future opt for using another AR provider, such as Junaio, as an indoor AR platform.

Design tour

The 'Design tour' project is the first step towards a sustainable and open AR platform for the museum. The first projects were mere one-off pilots, focusing on research and use of AR. With the design tour, the museum intends to create a platform that enables the museum to generate, adjust and improve its own AR tours. We expect to launch this project in March 2011.

The project consists of two parts: the interface for the public - the actual tour - and the content management system (CMS), through which the content of the tour can be maintained, adjusted and updated.

Content management system

By the conclusion of the main project, the CMS should be developed in such a way that it is an open platform, connected with the collection registration system of the museum, but also ready for use by other museums and institutions.

The CMS should be able to communicate with the Layar technology. However, since there are more players in the AR field, the system should be designed so that, with minor effort, it can also communicate with other AR providers.

AR is evolving, and new developments are commonplace. The challenge is to develop a sustainable system that is open enough to embrace these new developments and features.

The stories

As stated previously, developing (audio) tours is practically a core business for museums. When we started developing and writing the content of the design tour, naturally we followed the traditional method, as if for an ordinary audio tour. The tour had a real beginning and a definite end. Soon, however, we came to the conclusion that our presumptions were misdirected. The design tour should be more of a multi-narrative; it should inspire and engage the public to discover, learn, and interact with the design collection.

In the museum field, there are a few examples of AR application. As mentioned before, in most of them the reality is enriched with historic objects. An example is the Berlin Wall, positioned along its original division of the city. Another is at the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney, where visitors can see historical pictures placed in their original contexts.

Fig 10: The Berlin Wall is here again (in AR)

Fig 10: The Berlin Wall is here again (in AR)

The challenge for the Stedelijk Museum was not only to add this kind of historical content but also to primarily provoke a different kind of interaction between the user and the collection. In the case of the design collection, historical enrichment can be sufficient. However, in the context of a modern art collection, it is certainly not.

The design tour (although we rather would not call it a 'tour') consists of two sections that interact in different ways: together they

- Explore the history and significance of design for the Stedelijk Museum through narrative and visualization ('History on location')

- Provide a platform for audiences to explore what design is or means to them ('Your design!').

History on location creates an engaging dialogue between an historical site and the collection and history of the museum. Visuals, historical documentation materials, narrated stories, etc., are connected to a number of locations in the city of Amsterdam. This application is based on the historical enrichment principle.

Fig 11: Example of history on location. A bedroom designed by Gerrit Rietveld for the Harrenstein family

Fig 11: Example of history on location. A bedroom designed by Gerrit Rietveld for the Harrenstein family

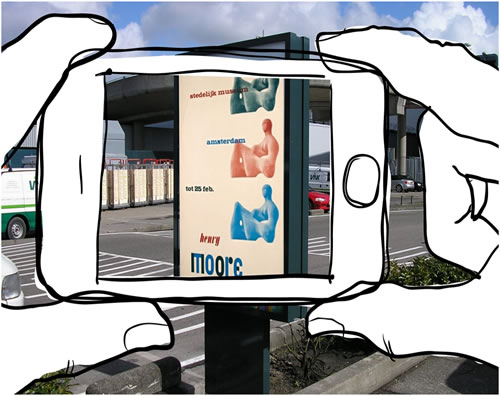

The Your design! part offers the audience interactive ways to see graphic design in its natural habitat, the original urban context. Visitors can pick up their favorite poster and post it wherever they like. The concept is similar to the ARtotheque project and has, aside from a few minor problems, generally proven successful. Additionally, participants can add their names and the reasons why they picked a certain poster and placed it at a particular spot.

Fig 12: Impression of the poster collection in public space

Fig 12: Impression of the poster collection in public space

Another concept of Your design! is sharing your domestic interior with others, similar to and sort of a follow-up to a famous Stedelijk exhibition of 1954, Wonen en wonen (Living and living). Other people then have the option to rate it, just as they did during the Wonen en wonen exhibition, when visitors were asked to vote for the room they'd most like to live in.

Development

We started developing this project in autumn 2010. We chose to develop it using an agile method, based on iterative and incremental development, where requirements and solutions evolve through collaboration between cross-functional teams. The main reason behind selecting this method is that it allowed for piecemeal development, something both easily and quickly adjustable when needed. Using new technologies asks for a flexible attitude from both developers and content providers.

4. Technology

Augmented reality is a relatively new and as yet evolving concept. The movie Minority Report, for which extensive research into the future was conducted, depicts some not-so-futuristic examples (information on translucent displays, gesture control, image recognition, facial/eye recognition, etc.). Developments in augmented reality are very much related to these 'futuristic' examples. Augmented reality is being implemented in experiments where a user wears a heavy computer connected to barely wearable displays (glasses and camera). The user can walk around and view and interact with his/her environment and virtually added objects. Currently three forms of augmented reality can be seen (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augmented_reality):

- head mounted displays (glasses with display and camera)

- handheld/mobile (using a smartphone or other handheld device)

- spatial (using a projector)

Head-mounted and spatial methods are still under development, and there is no significant commercial availability just yet. AR glasses are becoming more widely available, such as the Vizux line of products (http://www.vuzix.com/consumer/), while in spatial AR, Pranav Mistry of TED fame (2009) carries out interesting experiments.

Currently the following state-of-the-art and more widely available and accepted applications have emerged:

- webcam augmented reality

- mobile (or handheld) augmented reality

Webcam augmented reality

This is a relatively simple and static form of augmented reality. A user holds a recognizable figure, or two-dimensional code from an advertisement or product, in front of a webcam and the computer screen shows a positioned object. The user can turn the object or invoke animations by moving or turning the 2D code/figure. In a museum environment, this AR application can be appealing for sculptures, buildings and other objects.

Mobile augmented reality

Modern smartphones with camera, positioning (global positioning or GPS), internal compass and device orientation sensors, such as the iPhone 3GS or 4, have made mobile augmented reality possible. Several applications use these possibilities to overlay imagery on the camera view. A user activates such an application and looks through the camera to observe added reality. Currently the most widely used applications of augmented reality browsers are Layar (www.layar.com), Junaio (www.junaio.com), Wikitude (www.wikitude.org) and Acrossair (www.acrossair.com).

In terms of augmented reality browsers, the positioning of objects and information is currently based on the position and orientation of the device itself. This works well in outdoor situations, although the exact positioning of buildings, for instance, can be problematic. For indoor situations and more accurate positioning, image recognition is currently being added. Good examples of image recognition possibilities are Google Goggles (www.google.com/mobile/goggles) and the recently launched application Word Lens (www.questvisual.com). In the AR field, there are several interesting developments at the University of Oxford (2008). Junaio has integrated image recognition to enhance positioning, with an application called Junaio Glue. Layar has announced its intention to integrate image recognition;, however a release date has not yet been announced.

5. Future perspectives

The technologies that are needed to further enhance and integrate AR experiences are rapidly developing. Some of these developments are driven by commercial applications, such as e-commerce, gaming and electronic payments. Others are technological developments, such as more computing power for smaller devices, smaller high-resolution displays, smaller high-resolution cameras, and faster and better image recognition software. When these developments are integrated in new hardware and software, new and better possibilities will emerge. AR will develop from a gadget or geek perspective towards a more wide- spread, emergent phenomenon.

Better smartphones and (medium size) tablets

The development of both the iPhone and Android-based devices is rapid. More processing power, better displays and better cameras will create new demand and new or better applications. Tablets (larger display smart devices) with cameras will create interesting possibilities for indoor tours.

Better and more integrated mobile AR browsers

The current AR browsers are rapidly improving. Of the current systems, only a handful will survive or be taken over by parties such as Google or Apple. There will probably be no standard for these browsers, as HTML is standard for Web browsers. The burden of compatibility, however, will remain limited because these browsers need only certain and more or less standard data (positioning, URLs, images, 3D objects), which are intrinsically quite interoperable.

In the foreseeable future, AR browsers can be integrated in branded applications. Layar, for instance, has announced its Layar Player (http://layar.com/player). This will create a more seamless experience for the user, who will be able to stay within a specific museum application and still experience AR.

Image Recognition

The AR experience will be greatly enhanced by better image recognition through more computing power and better algorithms. Specifically, indoor positioning will be made possible without other means of identification or positioning, such as RFID or Wi-Fi triangulation. This will provide a multitude of engaging opportunities for indoor tours.

Indoor positioning

Indoor positioning is currently possible through Wi-Fi triangulation, Wi-Fi fingerprinting, code recognition (e.g. QR codes) or RFID. Code recognition is an intermediate solution, and will disappear when image recognition improves. Unique objects (and faces, for that matter) will become recognizable codes. RFID and other near field communication technologies will become of greater interest when smartphone payment systems emerge. Smartphones will be equipped with such technologies, which will in turn be heavily standardized, driven by commercial banking forces. Wi-Fi triangulation is probably also intermediate, to be replaced by far cheaper and more easily implementable Wi-Fi fingerprinting. With this technology, indoor positioning is based on the Wi-Fi signals at a certain location, which are previously measured and linked to locations. The fingerprint of signals is sent to a server and the location is returned.

Wearable displays

The further development of wearable displays will lead to a more integrated augmented experience. Instead of pointing a smartphone to see what else is in the immediate surroundings, a user simply puts on glasses with a display and camera (and tilt sensors, compass, etc.), that connects these to a wearable processor (e.g. a smartphone); the user can then freely walk around and experience the augmented environment. Translucent displays may even make the built-in camera obsolete, although it will still be needed for image recognition.

Spatial integration

With projections, AR can be a more social and shared activity. Wearable beamers are already commercially available, but deployments in the public space will probably be awkward for some time, or perhaps never even fully accepted. Experiments in this area, however, have the potential to draw new interest and insights, or be manifest as new forms of communication and interaction.

AR Gaming

Gaming in general is a big driver behind commercial and social acceptance of technologies. The Nintendo Wii is the living example of this. In 2002, gesture-based control was only seen in a movie; in 2006, it was widely available with the Wii. The current smartphones (or smart devices without calling capabilities, such as the iPod Touch) are already the most popular gaming platforms. This will evolve even further, and integration with AR and wearable displays will lead to new forms of more physical gaming. These forms can already be used - or the future end products can be used - to experiment in learning enhancement or to deepen the museum experience. Can you imagine groups of visitors invading a museum wearing identical dark glasses while making gestures with a wristband controller?

6. Lessons learned and next steps

By 2002, media guru Lev Manovich had already predicted that museums and artists would "take a lead in testing out the augmented space future," claiming that

having stepped outside the picture frame into the white cube walls, floor, and the whole space, artists and curators should feel at home taking yet another step: treating this space as layers of data. This does not mean that the physical space becomes irrelevant; on the contrary… it is through the interaction of the physical space and the data that some of the most amazing art of our time is being created.

In this paper we have shown that Manovich was right and that museums indeed are taking a lead in the exploration of augmented space, both inside and outside the galleries.

The ARtours project of the Stedelijk Museum is now at its halfway point. The four projects gave us insight into the subject of augmented reality and how to apply it to modern art to create an interesting and engaging museum experience. Based on this, we can already draw a few conclusions and make some suggestions:

- Be aware of the possible practical problems, e.g. available charged batteries, connectivity (3G) failure in case of a crowded event.

- In the case of an event, interaction between visitors will increase. It turned out not to be an individual experience, but an interactive and social experience instead.

- The AR technique stimulates a different perspective on art from artists and enables the exploration of new possibilities.

- Small experiments help designers to understand the opportunities and limitations of the AR technology.

- Participating in an event or using an event to launch your project generates (free) publicity.

- The younger public (20-30) doesn't have smart phones. This will however rapidly change over the next year.

- Using GPS indoors is subject to error sensitivity (placement of the objects at the correct locations).

- Agile developmental methods are best suited (unlike the outmoded waterfall model) to working with new technologies.

- The AR technology alone is not enough for a real user experience. Simply putting art in an AR layer is not good enough. It's all about the content.

Before the end of 2011, we strive to have a working platform, a content management system in which we can make various tours and add stories and media. This platform will be able to publish to different AR- browsers. We seek to share this platform with our peers and are creating business models to make this happen.

We will develop concepts that will seek dialogue with our visitors, reflecting on our collection and on the significance of augmented reality used by artists today. The Stedelijk Museum wants to be a frontrunner, constantly challenging artists and the creative industry to come up with great artistic and technological ideas, making wonderful user experiences and creating worthwhile events.

7. References

McCarthy, Anna (2001). Ambient Television: Visual Culture and Public Space (Console-ing Passions). Durham:Duke University Press, 2002.

Manovich, Lev (2002). The Poetics of Augmented Space. 2002, last updated 2005. Consulted January 24, 2011 Available: http://manovich.net/DOCS/Augmented_2005.doc

Pranav, Mistry (2009). The thrilling potential of SixthSense technology. 2009. Consulted January 24, 2011. Available http://www.ted.com/talks/pranav_mistry_the_thrilling_potential_of_sixthsense_technology.html

University of Oxford, Department of Engineering Science, Active Vision Group (2008) Parallel Tracking and Multiple Mapping. 2008. Consulted January 24, 2011. Available http://www.robots.ox.ac.uk/ActiveVision/Research/Projects/2008bob_ptamm/project.html