Wendy Ennes, The Oriental Institute Museum of the University of Chicago, and Christie Thomas, The e-CUIP Digital Library Project of the University of Chicago, USA

http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu

Abstract

Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) is a facilitation technique created by Abigail Housen and Philip Yenawine that uses art and artifacts to teach visual literacy using communication and critical thinking skills. Although VTS's facilitation strategy is designed for face-to-face instruction in the classroom, we asked the question, "Can these same strategies be used to create an educational Web site for student learners?" Three University of Chicago organizations, Chicago WebDocent, the eCUIP Digital Library, and the Oriental Institute Museum, set out to do just that.

Informed by VTS and funded by a National Leadership Grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services, the partners set out to build an educational Web site for teaching and learning about the ancient civilization of Mesopotamia – today's Iraq. Called Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History, our project's intent was to build a site that empowered students to learn about this ancient culture by using virtual images of artifacts in two ways: in a group setting with a teacher as guide, and independently. The challenge was to build a Web site that engages students while allowing them to learn in both instructional settings and to transfer the tenets of VTS from a traditional teacher-led instructional setting to a virtual, student-driven learning environment. The result is a Web site with three major components: a Learning Collection of teacher-selected artifacts from the Oriental Institute Museum's Mesopotamian gallery; an interactive archaeological dig called’Dig Into History,’ and an on-line course for K-12 teachers. Each of these products draws upon the tenets of VTS in different ways to create unique learning experiences that, when used together, provide a rich, constructivist learning experience for the student.

This paper will deconstruct our design process, outlining the decisions we made along the way and showing how those decisions were informed by VTS. We will present each of the three products and explain how each is uniquely supported by VTS and constructivist teaching techniques, and how the three components work together to present a complete instructional unit on Mesopotamia and visual literacy. The paper will share our acquired knowledge so that others wanting to create innovative Web sites that provide instructional and social context for their collections can also use VTS to inform their Web site development and design decisions.

Keywords: visual thinking strategies, constructivism, Web design

Introduction

Visual Thinking Strategies, or VTS, is an educational methodology for teaching and learning visual literacy that uses a work of art as a springboard for classroom discussion (http://www.vue.org/). Developed by museum educator Philip Yenawine and cognitive psychologist Abigail Housen, VTS is learner-centered and promotes the acquisition of critical thinking and communication skills by providing students with a structured means of making observations, solving problems, and communicating ideas about works of art. Although VTS's facilitation strategy is designed for face-to-face instruction in the classroom, we asked the question, "Can these same strategies be used to create an educational Web site for student learners?"

At the beginning of 2004, with the support of a National Leadership Grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services, three University of Chicago organizations, Chicago WebDocent, the eCUIP Digital Library, and the Oriental Institute Museum, came together to explore how best to build an on-line educational resource about ancient Mesopotamia, one that would be easily accessible to teachers and students nationwide. The project, Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History, (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/) marked the first time that all three organizations worked together, and each contributed their expertise to different facets of the project. Chicago Web Docent (http://chicagowebdocent.org/) builds Web-delivered, instructional materials for the K-12 educational community. The eCUIP Digital Library Project (http://ecuip.lib.uchicago.edu/) builds digital collections of source materials that support independent student inquiry and classroom instruction in K-12 classrooms. The Oriental Institute Museum (http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/default.html) is unique as it is the only archaeological museum of its kind in North America. Within its newly renovated galleries, it houses a major collection of artifacts from ancient Syria, Israel, Persia, Anatolia, Egypt, Nubia, and Mesopotamia.

Goals Of Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History

At the inception of the project, the collaborators met with a Teacher Advisory Board made up of ten educators from the Chicago Public Schools who assisted us in identifying a number of high-level goals for the project.

The first high-level goal of Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History is to relay to the K-12 audience the concepts behind the science of archaeology and the discovery of an ancient civilization as well as a develop deeper understanding of Mesopotamian history by using artifacts from the Museum’s collection. Since local, state, and national learning standards require all middle and high school students to study ancient Mesopotamia, this resource aims to provide teachers and students with a comprehensive view of the area we now refer to as modern-day Iraq. By building a rich historical resource we also hope to contribute to a better understanding of the present-day Middle East, a task that is extremely important in light of contemporary world events.

Another high-level goal of the project is to improve the quality of visual literacy in our nation’s schools through the study of ancient Mesopotamian artifacts. Toward this end, we wanted Visual Thinking Strategies to inform the on-line resource in such a way that it would encourage students to be active participants in their own learning process. We envisioned students becoming not only consumers of scholars’ and archaeologists’ interpretations of artifacts, but also interpreters of the artifacts themselves.

One more high-level goal of this project is to use technology as a medium to move the Museum from its role as a local storehouse and interpreter of artifacts to a dynamic international educational partner and disseminator of primary source materials. Also, incorporating a wide range of innovative learning technologies helps to facilitate unique, constructivist learning experiences for students.

Other goals include providing a model for the adaptation and repurposing of university research, Museum resources, programming, and learning theories into highly effective on-line educational tools.

Why Visual Thinking Strategies

Using Visual Thinking Strategies to help drive the design of this project seemed a natural fit to the partners and members of the Teacher Advisory Board. VTS is a proven method for visual literacy instruction presented by Visual Understanding in Education (VUE), an organization that conducts educational research and publishes curricula (http://www.vue.org/). In 2003, Wendy Ennes and Carole Krucoff from the Education department of the Oriental Institute Museum participated in a seminar with Philip Yenawine to learn the VTS method. It seemed a logical next step to try to find a way to integrate Visual Thinking Strategies into the on-line ancient Mesopotamia resource that we were going to begin to create in 2004.

The face-to-face VTS method begins by showing an artwork to a group of students and asking them the leading question, "What is going on in this painting, drawing, or sculpture?" Students respond by looking closely at the artwork and answering the question. As each student answers, the teacher, without judgment, restates or paraphrases the student's observations to the class while pointing out the visual evidence of the student’s opinion as evidenced within the artwork.

As the discussion evolves, the teacher or facilitator continues to move it along by asking, where appropriate, two more open-ended questions: "What do you see that makes you say that?" and "What else can you find?" These three key questions can be used while on a field trip to a museum or within a classroom setting using a reproduction or projected image. An added benefit of VTS is that the teacher or facilitator need not be an expert in art or art practice. The informal discussion format of a Visual Thinking Strategies session allows students to communicate and construct their own interpretations while learning from peers as the group moves through the process of decoding a work of art. In its purest form, Visual Thinking Strategies is an easy to use, face-to-face constructivist teaching tool that encourages novice museum/art-goers to build ideas and concepts as a group together.

Encouraging students to become interpreters of artifacts and active learners is a core tenet of Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History’s programming goals. VTS has a proven method for teaching many of the same skills we aim to translate to our users with our Web-based materials. Interpreting VTS for use on the Web began with us striving to create a Web site with ancient Mesopotamian artifacts. As the project evolved it quickly moved beyond our original goals to include exploring and reinterpreting the ways in which the Web itself can provide VTS-inspired instruction.

Questions that arose when planning the outcomes for this project included How do we encourage the use of Visual Thinking Strategies with a Web-based resource? How do we translate the tenets of VTS, a face-to-face facilitation technique, into Web-based instruction? How do we get students and educators to go beyond simply looking at an object and begin to extract meaningful information from it? How do we encourage them to draw unique conclusions? And, How do we extend and amplify the teachable moment of an artifact by using VTS?

As the collaborators and teacher advisory board members strove to answer these questions and define our project, additional questions arose as to how to make the project different enough from other resources on the Web about ancient Mesopotamia. Our survey of on-line materials and feedback from our Teacher Advisory Board told us that there was a severe lack of age- and learning-appropriate resources about ancient Mesopotamia on the Web. We realized that just by building the resource, we were filling a much-needed gap, but we also wanted to create a unique learning experience where students would be driven beyond information gathering and what could be typical rote recollection of content to becoming scholars and curators themselves - we wanted to make ancient Mesopotamia as engaging as possible.

Another challenge included making the Museum’s collection more accessible and understandable. We can put the Museum’s collection on the Web and provide virtual access to it, but how can the Web make it easier for students to understand how archaeologists interpret knowledge? Scholars and archaeologists generated the information that students read, but we also know that it is important to allow students to interpret the artifacts and challenge what they are reading. Such an approach would make them generators of knowledge themselves. If we were successful at doing this, we could exponentially increase the intellectual accessibility of all museum collections.

The Web Resource

With the flexibility of Visual Thinking Strategies as one of the key conceptual underpinnings of the project, the partners moved ahead as a team to create the three main components of the Web site. The first component, a searchable database of teacher-chosen artifacts from the Mesopotamian Gallery called the Learning Collection, was developed by the eCUIP Digital Library Project. The second is a Flash® interactive created by Chicago WebDocent that uses artifacts from the Learning Collection to explore the concepts behind the science of archaeology and the discovery of ancient Mesopotamian civilization. Lastly, the on-line professional development distance learning course for educators draws upon content approved by University of Chicago faculty as well as the framework of the Learning Collection, and the Flash interactive. Personnel at the Oriental Institute Museum developed the on-line course.

Each of the three core components draws upon the tenets of VTS in very different ways. Due to the unique structure of each component and the way they mesh together, a wide range of learning experiences is created. These vary and are successful because they engage users in new and different ways. When they are used together in a cohesive teacher-created lesson plan, they complement each other and provide rich, constructivist learning experiences for students and educators alike.

Developing the Learning Collection

The Learning Collection provides a searchable and browseable interface to a group of teacher-selected artifacts from the Oriental Institute Museum’s Mesopotamian collection. All aspects of the Learning Collection were impacted by the team’s decision to create a resource that supports Visual Thinking Strategies instruction. Since members of the Teacher Advisory Board received VTS instruction prior to choosing the artifacts, VTS ultimately guided the selection of the artifacts. Additionally, the metadata schema that supports the Learning Collection is based on Dublin Core with controlled vocabularies that support educational use of the collection and also VTS instruction. Finally, the interface for the Learning Collection was designed to support face-to-face Visual Thinking Strategies instruction and actually provides VTS instruction virtually for those students approaching the resource without teacher guidance.

Early in the project, Karen Wilson, the Curator of the Mesopotamian Gallery, began the selection process by creating a list of relevant artifacts that fit within the goals of the project. Aligned with the categories found in the Oriental Institute Museum’s teacher’s guide, Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, the list was narrowed down to fifteen artifacts for each of the fourteen categories. These categories were chosen to represent the culture of ancient Mesopotamia in its entirety: Archaeology, Prehistory, The First Farmers, The First Cities, The Invention of Writing, Literature, Mathematics and Measurement, Law and Government, Religion, Architecture, Daily Life, The Role of Women, Science and Inventions, and Warfare and Empire. The Teacher Advisory Board then narrowed down the selection of artifacts to ten in each category by choosing those artifacts that would be most engaging to students, by their ability to educate the students, and by how well they illustrate the concepts of the categories. The final list of one hundred and forty-four artifacts became the core content for the Learning Collection.

When designing the interface for the Learning Collection, we were driven by two leading questions. How can we build an interface that supports face-to-face VTS instruction? How can we incorporate the tenets of VTS into the presentation of the artifacts for independent student inquiry? We developed the interface in such a way that users can access the collection in three ways: through a traditional search interface, through a visual interface that requires students to select an artifact simply by looking, and through various browse features based on teacher-selected categories. Furthermore, we developed two different artifact information pages that allow users to toggle between the two to access information about the artifacts in different ways. The Artifact Description page includes curatorial information about the artifact, an artifact description, and suggested readings.

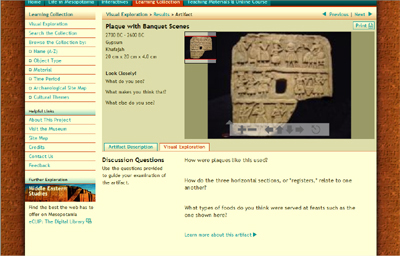

Fig 1: The Artifact Description page for “Plaque with Banquet Scenes” from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Learning Collection (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/learningcollection/search.php?lcid=101&&b=96)

The Visual Exploration page is designed to encourage students to look at the artifacts for answers and not the text. This page leaves out the descriptive information about the artifact and instead lists questions about the artifact. The questions were designed as conversational prompts for face-to-face VTS instruction or as guides students as they approach the artifact individually. After looking at the artifact and interpreting it by using VTS questions as a guide, students can toggle to the Artifact Description page to learn what scholars and archaeologists say about the artifact.

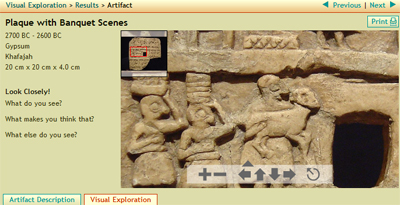

Fig 2: The Visual Exploration page for “Plaque with Banquet Scenes” from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Learning Collection (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/learningcollection /search.php?lcid=101&view=visual&b=96)

The visual and browse interfaces are unique aspects of the Learning Collection because their design is heavily informed by VTS. To meet the goals set by our incorporation of VTS, the visual and browse interfaces had to move beyond traditional browse interfaces. The Visual Exploration interface is a collection of thumbnails of all of the artifacts in the collection: the interface encourages students to select an artifact for inspection based upon its physical properties. When students select artifacts through the Visual Exploration interface, they are taken directly to the Visual Exploration page that houses the leading VTS and discussion questions. Their interpretation of the artifact is dependent upon looking and not upon the interpretations offered by scholars and archaeologists.

Fig 3: The Visual Exploration artifact selection interface from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Learning Collection (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/learningcollection/index.php?a=visual&b=96)

To further the goals of Visual Thinking Strategies, the browse interfaces were given interactive, visual designs as opposed to the more traditional text-based interfaces. This provides a social context for their discovery and encourages students to look at the artifacts and make connections between them. Two excellent examples of this are the time period and archaeological site map browses. The time period browse interface presents a graphic timeline that allows the student to select a time period with visual clues to the type of artifacts they will find in that area of the timeline. The archaeological site map browse interface presents students with a map of the region. It allows them to select a location or many locations from the map and view artifacts from those archaeological sites.

Fig 4: The Time Period browse interface from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Learning Collection (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/learningcollection/index.php?a=timeline)

Fig 5: The Archaeological Site Map browse interface from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Learning Collection (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/learningcollection/index.php?a=site)

One of the most important decisions we made was to use the Zoomify interface for the artifact images. Zoomify is a technology that makes it easy to deliver high resolution images on the Web. The Zoomify interface includes a tool palette that allows users to manipulate the image, zooming in on it so that they can examine the artifact in detail. It also includes a tool that enables a user to move around the canvas and focus in on different aspects of an artifact image. We chose to use Zoomify because it assists us in achieving many of ourhigh level VTS goals. The Zoomify interface is successful at allowing and encouraging users to spend time looking at an artifact up close.

Fig 6: The Zoomify interface from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Learning Collection (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/learningcollection/search.php?lcid=101&&b=96)

Using Visual Thinking Strategies in a Flash Interface

The use of VTS can also be found at the very heart of Dig Into History. Dig Into History is the in-depth educational Flash interactive that was created to complement the Learning Collection It was also developed for those teachers who wanted a quick and effective way to educate their students about the history of ancient Mesopotamia without requiring them to first wade through the Learning Collection. For this reason the interactive needed to stand alone as an educational tool. The interactive was born out of the museological concepts of collecting, classifying, and curating. During the first years of development, we all referred to it as Collect, Classify, Curate.

The Chicago WebDocent team is experienced at creating in Flash stand-alone instructional units that can be used effectively and easily within the context of a classroom period. Dig Into History was designed to be a unit of instruction that would encourage observation and critical thinking skills while relaying the concepts behind the science of archaeology and knowledge of ancient Mesopotamian civilization through artifacts from the Mesopotamian Gallery of the Oriental Institute Museum. We had broad concepts and a large amount of material we wanted to convey within such a compact educational vehicle.

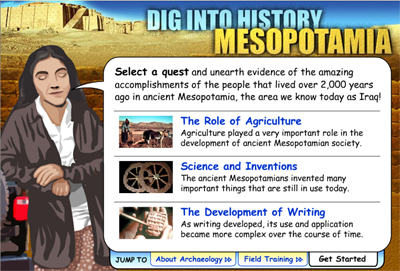

After many discussions the project team and teacher advisory board members developed for Dig Into History an interface that supports all of the high-level goals we had established for the project. Well-suited for the middle school audience, Dig Into History feels like a game because it allows students to choose a quest and go on a simulated archaeological dig in real time. But, in fact, it is much more than that. What seems like an archaeological game actually leads to expanded lessons on the skills encouraged by Visual Thinking Strategies as well as the implementation and integration of those all-important literacy goals that educators desire.

With three statements to choose from and clues that lead them to the successful discovery of artifacts, students are challenged further as game play shifts and the interface becomes more of a tool that records their own discoveries and insights. Students move through the game as project managers with the guidance of a mentor. They dig for artifacts, fly by helicopter between three different dig sites, and choose whether or not to take the advice of their mentor. They are propelled to find ancient Mesopotamian artifacts that support a quest statement that they chose at the beginning of the game.

Fig 7: Select a Quest page from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Dig Into History (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/interactives/DigIntoHistory.html)

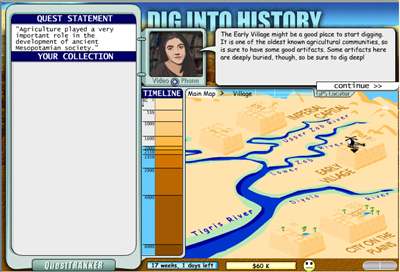

Fig 8: Dig site selection screen from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Dig Into History (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/interactives/DigIntoHistory.html)

A student who has located an artifact is prompted to catalogue it and collect information about it from the screen. Cataloguing includes identifying where it was found, its age, and the material it is made of, and composing free-form notes about the artifact. Zoomify is used again in the Flash interactive so that students can view the artifact up close. The use of Zoomify software within the Flash interface helps support a more refined VTS experience because student users are required to examine the artifact up close. Game play advances only if the student observes and then composes a detailed written description about each artifact. Upon the successful recovery of at least four artifacts, the student can pause and print up a field report, continue to unearth more artifacts, or move ahead to the next step of creating an exhibition.

Fig 9: Catalog an artifact screen from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Dig Into History (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/interactives/DigIntoHistory.html)

The field report is a printable HTML file that serves as documentation for teachers of their students’ work and writing skills. It includes the overarching quest statement that each student chose at the beginning of the game, an analysis of the student’s skills as a project manager, as well as photographs of the artifacts discovered and the student’s unique written observations about each artifact. There is also a code generated for each separate field report; a student can use this to move to the next stage of game play - curating personal exhibition in a virtual museum.

The Curate a Museum Exhibition feature of Dig Into History builds upon the Visual Thinking Strategies and literacy goals of the Collect and Catalog Artifacts experience. Players choose four artifacts that best illustrate and support the original quest statement they chose at the beginning of the game. The students learn by doing. They learn about the structure of a museum exhibition by participating in the development and creation of a curatorial premise as they write and edit museum labels for each of their artifacts. Again, embedding the Zoomify interface within the interactive encourages students to look closely at each artifact and examine it carefully as they compose their museum label.

Fig 10: Curate a museum label screen from Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History Dig Into History (http://mesopotamia.lib.uchicago.edu/interactives/DigIntoHistory.html)

Visual literacy and literacy skills are inspired through every step of the process as each student creates a unique virtual museum exhibition. This exercise culminates in a scrolling exhibition complete with artifact labels and a curatorial introduction created solely by the student. And, just like the field report, the exhibition includes photographs of the artifacts, the curatorial introduction, and the artifact labels in a printable museum catalog of the student’s show. The catalog is flexible enough for teachers to use as a gradable outcome of a student’s performance.

Using VTS Within an On-line Professional Development Course for K-12 Educators

The final feature that was created for Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History is an on-line professional development course developed for K-12 educators nationwide who wish to earn graduate credit while learning about ancient Mesopotamia. Visual Thinking Strategies is introduced immediately within the first module, and on-line participants will undertake studying it during the first week of the course when it is offered in the fall of 2007.

On-line course participants first start by reading PDFs about VTS. They download these from the Visual Understanding in Education (VUE) Web site (http://www.vue.org/). Since VTS is an instructional tool, one of the many outcomes of the on-line course is that teachers will be required to submit a final lesson plan project. The plan will include requisite literacy goals and the use of at least two components of the resource: VTS, the Learning Collection, or the Dig Into History interactive. Teachers will also participate in a discussion board, answering questions about VTS and its applicability in the classroom. Predetermined discussion groups will also participate in a real time exercise by analyzing Mesopotamian images using VTS in the Blackboard chat feature.

Usability and Evaluation

Upon completion of the Learning Collection and Dig Into History, project staff conducted a usability study to identify bugs within the program and gauge whether or not the design of the products met our initial goals. The study was conducted with twelve sixth grade students at a Chicago Public School. Over two days, six of the students were observed using Dig Into History and engaging with a paper mock-up of the Curate section as this interactive was incomplete. Six different students were observed using the Learning Collection. The next section summarizes our observations that shed light on the achievement of our learning goals for the products.

Overall, the students were able to access and use the Learning Collection without much guidance. While completing the study tasks for the Learning Collection, the students spent time looking at the images instead of glancing at them and clicking on to the next image. They liked the interactive browse features and needed prompting to look at other browse features because they were so engaged with the one they were currently using. When viewing the Visual Exploration page that uses questions to engage the students in looking at the artifact in detail, the students were confused by the questions and needed prompts to look at the image for the answers. They had expectations that there would be text that contained the answer. They also expressed concern about answering the questions incorrectly. These responses suggest that face-to-face VTS instruction might be more effective with students than independent Web-based VTS instruction. We concluded that students might find Web-based VTS instruction more natural after experiencing at least one session of face-to-face VTS instruction with their teacher. We are reexamining ways that we can modify the resource to help students incorporate the VTS questions into independent examination of an artifact.

During the study, the students found Dig Into History a fun and engaging means of learning about ancient Mesopotamia. Many of the students’ expectations for Dig Into History were founded on their experience playing video games in other areas of their lives. The students were immediately able to grasp the concepts of the interactive game and begin play. The students commented that using Zoomify made them want to look more closely at the artifact and that it helped them draw conclusions about the use of the artifact. Students spent a lot of time looking at the artifacts once they mastered the Zoomify interface (which we modified to make it easier to use after the study). They really liked finding the artifacts and digging for them. One student commented that, “This is just like what an archaeologist would do.” They also enjoyed cataloguing the artifacts and answering the questions about them. They again expressed concern about answering the open-ended questions incorrectly. The students used the interactive as a group and engaged in a lively debate over the interpretation of each of the artifacts. The students were creative and imaginative when writing descriptions of the artifacts. Once they were assured that there were no incorrect answers, they enjoyed looking closely at the artifacts and making their own observations about the artifacts.

In the Curate a Museum Exhibition portion, students were mindful of the selection process, and choice was very important to them. They enjoyed being able to choose the artifacts that they wished to examine more closely. One student commented, “I liked being the historian and writing the descriptions.” We concluded that use of the Zoomify tool was an integral part of the interpretive process on the Web. As mentioned earlier, visual literacy and literacy skills are inspired through every step of the curatorial process as each student goes about creating a unique virtual museum exhibition. The usability and evaluation study demonstrated that the resource was fun and easy to use. The resource led students to spend time looking at artifacts in detail, to draw their own conclusions, and learn more about ancient Mesopotamia.

Conclusion

The project team that created Ancient Mesopotamia: This History, Our History set out to build a Web-based resource that would be successful at encouraging the K-12 audience to examine artifacts they might not ordinarily have the opportunity to view. We also wanted to create a resource that supported the latest research by scholars and archaeologists, and one that was flexible enough to facilitate user-created interpretations of the artifacts. The Visual Thinking Strategies methodology gave the project the necessary instructional framework. VTS provided the model for meeting the educational goals of the project. Together, the Learning Collection, Dig Into History, and the on-line course create a comprehensive resource. By promoting the acquisition of visual literacy and literacy skills, this resource facilitates teaching and learning about ancient Mesopotamia in an innovative way.

Cite as:

Ennes, W., and C. Thomas, Integrating Visual Thinking Strategies into Educational Web Resources, in J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings, Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2007 Consulted http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/ennes/ennes.html

Editorial Note