Introduction

Artists are always drawn to technology, and from the early days in the development of real-time 3D virtual environments, digital artists have been exploring the possibilities and testing the boundaries for art creation and display on these platforms. The media hype surrounding Second Life in 2006 prompted several intrepid cultural institutions to colonise an island and begin to explore the opportunities 3D virtual environments offer museums and galleries. There have been several studies of the potential for multi-user virtual environments (MUVEs) to embellish, extend or enhance the physical museum experience; to enable experimentation, interaction and engagement with material art or museum objects that would not be possible in 'real life' (Urban, 2007; Rothfarb & Doherty, 2007). Nevertheless, few have considered the advantages, and disadvantages, of Second Life as a display platform for digital art or the role cultural institutions may play in this environment.

Many of the galleries that have been constructed in Second Life reflect an intrinsic reliance on the physicality of the gallery building, the collection it houses, and the cult of the art object, all historically crucial aspects to a museum or gallery's function but all elements that can limit the potential for exhibitions of digital art in its native environment. One of the most impressive examples of the imitative virtual display methodology can be found at the Dresden Gallery Island (http://www.dresdengallery.com/) where all the rooms of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister have been painstakingly reconstructed, true to scale and down to the tiniest detail, complete with scanned reproductions of all 750 masterpieces in the permanent collection. While the experience of navigating an avatar through what feels like a magnificently constructed doll's house is quite novel, it could be argued that reproductions of the works would actually be better viewed statically on a Web page, free from the often frustrating lag or clumsy avatar navigation skills.

This paper outlines the National Portrait Gallery's implementation of Second Life as a display platform for original digital artworks, and considers ways cultural institutions can employ 3D virtual environments to critically engage with art forms that challenge traditional display and collecting methodologies.

Background

The National Portrait Gallery (NPG) in Canberra, Australia, was established only eleven years ago, managed by a staff of twenty, and housed in the library of Old Parliament House. In December 2008, the staff (now numbering 52) and a growing permanent collection relocated to a purpose-built gallery constructed in the arts precinct. Despite spending most of its young life housed within a heritage building, from its very inception the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) has actively challenged preconceptions surrounding notions of identity and traditional views of portraiture.

Similar to the Portrait Galleries in Washington and London, the NPG in Australia has predominantly figurative works on display;, however, given the age of the institution, the vast majority of its portraits are contemporary. Indeed, the very first commissioned work of art for its newly established permanent collection in 1999 was the exuberantly psychedelic spray portrait of Nick Cave by Howard Arkley. The collection has also expanded to include animations, video portraits, landscapes and abstraction.

Taking its lead from this underpinning philosophy, the National Portrait Gallery's on-line exhibition program was established to develop exhibitions that interpret and analyse concepts of identity and representation through the display of works of art which exploit the unique qualities presented by the digital environment. In addition to its marketing, information and audience engagement functions, the NPG's Web site is considered an exhibition space in its own right and is included as part of the Gallery's overall exhibition programming and development.

The National Portrait Gallery's first on-line exhibition Animated: Self Portraits Online, launched in 2007, was a solely Web-based display of original animated self-portraits by fourteen Australian artists (Archived Site: http://www.portrait.gov.au/animated/). Animated was, in fact, the flagship exhibition for the National Portrait Gallery at that time, as the physical gallery was closed in preparation for the relocation to the new building.

Based on the success of Animated,the on-line exhibition program was expanded for the doppelgänger exhibition to include a physical display component in two multimedia rooms within gallery space in Canberra. This provided the NPG with the opportunity to experiment with methods of displaying on-line art to a general public within a conventional exhibition space.

Seeing Double

Exhibition Development

The doppelgänger exhibition was conceived as a display of original digital artwork which would explore the concepts of constructed self, identity, beauty, truth and illusion in the digital realm. The exhibition brief specified that the artist's response was not to be confined to a physical likeness in the traditional sense of a portrait, and the idea of the doppelgänger in the exhibition could take on many forms, as simple or complex as needed, to create a compelling expression of the central exhibition theme. It also specified that there was no need for an active presence and that an environment could also create a de-facto portrait.

The themes of the exhibition were considered to be perfectly supported by the selection of a 3D virtual environment as a display platform which required potential audiences to participate in the act of creating a doppelgänger, in the form of an avatar, in order to view the display.

Second Life was selected over alternative 3D virtual environments primarily on the basis of population, both of potential audience and the number of practising artists operating in this space. Despite the recent well-publicised withdrawals of large corporations from Second Life (Hearn, 2009), and renewed media debate about the long-term sustainability of a platform that is based on a capitalist model, the base population statistics are still on the rise, and the artistic and education communities are continuing to increase (Linden, T. 2009).

Five digital media artists from Australia, USA, Italy and China were commissioned to produce original works of art for the exhibition, for which the majority of planning meetings took place in Second Life.

The works of art created for the doppelgänger exhibition are by their very nature ephemeral, multimodal and performative, presenting significant challenges to traditional display and interpretation mechanisms conventionally used by museums and galleries. The following section examines three of the works which exemplify two emerging trends in the creation of digital art in Second Life: Second Life based works which address the simulacra of virtual worlds from within; and mixed reality works which slip around across multiple platforms and refuse to be confined by the boundaries of the program.

iGods, Autoscopia and CodePortraits

Gazira Babeli is recognised internationally as one of Second Life's most prominent artists; however, she only exists within the Second Life environment. The artist behind the avatar has deliberately dissociated her real life identity from that of Gazira, preferring instead to let Gaz's actions speak for themselves. Gazira's performances challenge the 'illusions' of Second Life whilst disrupting its very fabric and for this reason have frequently been interpreted as 'griefing' attacks (Talamasca, A. 2006). Her performative work, iGods, sets up seven clones, or 'bots' in an ancient Greek-styled temple which, upon approach, morph into a replication of the visiting avatar's appearance. The work reminds the viewer that, in Second Life, DNA is code and in virtual worlds this code can be replicated or borrowed. Interestingly, the work raised concerns regarding copyright violation and a notice had to be added to the label accompanying the work in Second Life to reassure visitors that no data was captured or stored in the code replication process.

Fig 1: Patrick Lichty's avatar experiencing Gazira Babeli's, iGods on Portrait Island. Image courtesy of the artist

Autoscopia, created by Adam Nash, Christopher Dodds and Justin Clemens,is a complex investigation and interrogation of the notion of data as a conduit of identity. While created specifically for the Second Life environment, it operates across many platforms and opens up multiple interaction points within the work. In Second Life, an avatar approaching the work is invited to enter a name into a search engine which runs a deep Internet search retrieval of all the associated public data. The resulting data is used to build a real-time audiovisual sculpture, the size, colour and volume of which is directly proportionate to the amount of information retrieved. The work publishes a Web page containing the composite data and a photograph compiled of all tagged images associated with the particular name (http://www.autoscopia.net). The Web page then tweets its presence, further adding to the cacophony of data proliferated on the Web, all of which feeds back in to the next autoscopic search undertaken on that particular name.

Fig 2: Autoscopia by Adam Nash, Christopher Dodds and Justin Clemens. Audiovisual sculpture built from data retrieved from a search on the name 'Barack Obama'

The artists addressed the representation of their work in the physical gallery spaces through the development of a composite group portrait in both digital print and video format which conveyed the theme of the Second Life work without a direct translocation of the virtual into the physical. The final component to the Autoscopia project is an essay written by Clemens, downloadable from the NPG's doppelgänger Web site, which is written using the same 'autoscopic techniques' demonstrated in the activation of the digital work.

Fig 3: Multimedia interpretation of Autoscopia developed for the physical exhibition space. Image courtesy of the artists

Patrick Lichty's CodePortraits also resist containment by the display space in Second Life. Referencing Andy Warhol's 1960s screentests, Lichty's short videos of friends, colleagues and artists he has met and worked with in Second Life form a collective self-portrait of the artist's virtual life. The films themselves are not displayed in the Second Life exhibit, but rather are made available via Quick Response (QR) codes which audiences in Second Life and visitors to the physical display at the NPG in Canberra can decode and download using their mobile devices.

Fig 4: Patrick Lichty's CodePortraits on display on Portrait Island

Design of Portrait Island

The design and development of the display space for the doppelgänger exhibition presented the opportunity to break the model of replication employed by so many galleries in Second Life and to develop a flexible environment that would experiment with the unique opportunities presented by virtual architecture.

Portrait Island was developed with the underpinning philosophy that 3D virtual environments, freed from physical display considerations such as walls, lighting, air-conditioning and gravity, can be effectively designed to facilitate the visualisation of shared, networked, information spaces.

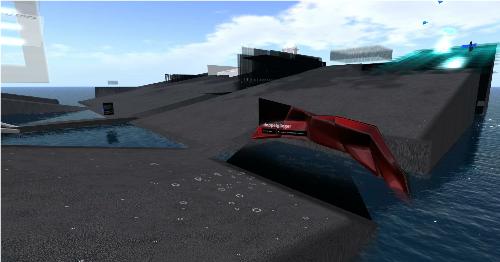

Portrait Island is designed as a singular and monumental inclined plane - that is cut and formed - to create a series of unique exhibition environments. Conceptually the design of Portrait Island responds to the condition of the monument in the landscape - so noticeable in the public institutions of Canberra - by simply inverting it. The landscape becomes the monument. This inversion denies the representational norms of virtual worlds, allowing the works developed for the doppelgänger exhibition to form the landscape, rather than being objects within one. [More, G. 2009 Portrait Island design statement]

Fig 5: Portrait Island designed by Greg More of OOM Creative. Image courtesy of the designer

The exhibition spaces on Portrait Island range from two traditional spaces, recognisable as the typical 'black box' or 'white cube' galleries, to a series of open-ended environmental features which reflect the ethos of the exhibition and are continuously evolved to complement the artworks. The island is never static - it was moulded and manipulated throughout the installation phase, and this evolution continues, post-launch, in response to observations of audience navigation and feedback.

Acknowledging the inherent social nature of virtual worlds, communal gathering spaces for congregating tour groups and virtual forums have been incorporated into the design of Portrait Island.

Fig 6: Forum space for group lectures or communal gatherings

Metrics systems installed throughout the space enable the exhibition designer to monitor the movement of avatars throughout the landscape and gauge the navigability of the island either as a whole, or broken down into its component display areas. Standard quantitative data captured to date indicate a high visitor engagement, with an average visit length of approximately 50 minutes. Preliminary trends also indicate a very high level of re-visitation, and solo visitors often return with companions, reinforcing our understanding of Second Life as an inherently social space. The metrics system also provides the opportunity to gauge such aspects as exploration throughout the 3D plain (taking into account the ability of avatars to fly and walk under water), teleporting entry and exit points, and geographic visitation statistics.

Qualitative data is being collected from community participation on blogs, forums and twitter. However, interestingly, there has been very little take-up on the qualitative feedback forms which were embedded into Portrait Island near each artwork.

Analysis of these statistics is ongoing, and a more complete evaluation will be possible once the exhibition closes.

Exhibition communication

As previously discussed, not only do several of the works in the doppelgänger exhibition operate across multiple digital platforms, but in order to address the barriers to participation potentially presented by the Second Life environment (hardware, bandwidth and security network considerations), the communication of the exhibition itself also had to operate on several different tiers. The primary site of the exhibition is Portrait Island, but the works are also reproduced on the National Portrait Gallery's Web site, in the multimedia exhibition spaces at the physical gallery, and via several social networking channels (Flickr, Youtube, iTunes).

The doppelganger subsite (www.portrait.gov.au/doppelganger) is the hub of information about the exhibition and forms the common nexus for both Second Life and non-Second Life audiences. The Web site can be accessed from multiple points throughout Portrait Island and viewed via the Second Life Web browser. Alternatively, external audiences can sign up for Second Life and teleport directly to the Island via links on the exhibition subsite. The subsite provides information on the themes of the exhibition, the artists and their works, the design of Portrait Island, as well as access to the Flickr group, machinimas syndicated via YouTube, and podcast interviews with the artists available for streaming from the site or downloaded from iTunes.

The National Portrait Gallery and other galleries developing on-line exhibitions are still experimenting with the best ways to incorporate mixed-reality displays in their physical gallery spaces. Some physical exhibitions of art in Second Life have employed 'bridging' techniques to assist audiences to quickly gain an appreciation of the display platform, before moving on to communicating the concepts underpinning the exhibition itself. For example, the Babelswarm (http://www.babelswarm.com/) Second Life exhibition displayed at Lismore Regional Gallery in 2007 oriented visitors through three separate spaces, beginning with a display of text and printed photographs of the exhibition, moving through to a room containing machinima of the work, and ending in a larger space with real-time projection where the artwork in Second Life was created from the voices of the real life audiences in the gallery space (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=310VNpNvHVM&feature=player_embedded).

For the display of doppelgänger in the physical Portrait Gallery, the artists were asked to produce stand-alone multimedia interpretations of their works which would facilitate access to the themes addressed in their art and complement the Second Life display. The responses ranged from recorded machinima, live streaming of the work observed through the eyes of a scripted avatar, printed Quick Response codes with accompanying videos, and the composite print and video portrait of the three artists collaborating on Autoscopia (Fig. 3).

The NPG was unable to provide public access to the exhibition via computer terminals in the building due to the difficulty of restricting avatars from teleporting away from Portrait Island. Second Life requires users to be over 18 years of age, a policy which would be impossible to police in the public spaces of the Gallery. Following the launch of doppelgänger, Linden Labs announced the development of a 'behind-the-firewall' version of Second Life, Nebraska, which was developed for companies who wish to create a restricted access island for internal use, not connected to the main Second Life grid (Linden, A. 2009). Preliminary investigations of this product suggest that while it could provide a solution for public access via computer terminals set up in the gallery, the costs associated with its establishment would have been prohibitive for the National Portrait Gallery's project. Similarly, the replication of the exhibition on Teen Second Life (http://teen.secondlife.com/) was also considered as a mechanism for enabling all ages access to the exhibition. However, aside from the additional pressure this posed the exhibition budget, the human resources required to effectively engage with two Second Life communities was beyond the scope of the staffing for the project.

Computer terminals with live access to the exhibition were provided, however, for the physical launch of the show at the Gallery. Attended by over 250 visitors, the launch party featured a virtual launch address given by the National Portrait Gallery Director's avatar from within Second Life and projected on a large screen in the Gallery's entrance hall.

Fig 7: Visitors at the physical exhibition launch at the National Portrait Gallery, 23 October 2009. Image courtesy of Mark Mohell

Multimodal marketing & community engagement

To promote the doppelgänger exhibition, the National Portrait Gallery employed a mixture of traditional marketing techniques and more community-focused participatory Web and social media strategies. Somewhat predictably, the take-up by print and broadcast media focused on the novelty value of 3D virtual environments; however, in most cases, the message that this exhibition was not simply about the display platform was recognised in the resulting articles (AAP, 2009).

doppelgänger was promoted in Second Life through notifications sent to established artistic communities, some of which have well over 1000 members, and through specialist blogs and community Web sites and forums. Due to the restriction on the number of avatars that can occupy an Island at any given time, a series of special group previews for the large and active artistic communities established by Second Life promoter Bettina Tizzy were arranged, in addition to an official virtual launch of the exhibition. Second Life is an inherently social space, and the initial success of the launch of the exhibition relied heavily on the reputation of the participating artists and less on the reputation of the Gallery itself, which had no established history in this environment.

With the advent of the participatory Web and social media, galleries and museums have been forced to consider the sustainability of institutional participation in these spaces (Russo, 2008), and ongoing and meaningful engagement with audiences in Second Life is no different. It comes as little surprise that cultivating relationships with any community is resource-and-time intensive, and must continue beyond the establishment of an institutional presence. Throughout the exhibition, the National Portrait Gallery has increased its visibility through the constant involvement of Gallery staff in the Second Life artistic communities, and plans to continue to cultivate the display of digital artworks on the Island following the close of the doppelgänger exhibition.

Conclusion

Pierre Bourdieu's theory of the cultural field examines the symbiotic relationship between individuals and institutions involved in making cultural products what they are: the writers, artists, publishers, critics, dealers, galleries and academies (Bourdieu, 1993). While writers, artists, publishers and critics are engaging with new and emerging forms of digital art created in 3D virtual environments, dealers, galleries and academies, with a few exceptions, remain noticeably committed to the object and to material concerns.

Cultural institutions continue to grapple with the difficulty of imposing object-centric models of display, access, copyright, acquisition and archiving, on digital art (in itself an inadequate label). However, increasing numbers of artists are producing significant works in on-line networked environments without the support and validation of the gallery sector, the marketing power of branded organisations, or the links with off-line arts communities.

The doppelgänger exhibition has enabled the National Portrait Gallery to examine what role it may play in digital environments, to engage with a new breed of digital artists, to challenge traditional audiences, to expand its own reach in terms of geography and demography, and to update the concept of a portrait to take into account the opportunities of the digital age.

References

AAP. (2009). Exhibition explores online identities. 23 October 2009 consulted January 30 2010 http://news.ninemsn.com.au/entertainment/919479/exhibition-explores-online-identities

Allison, J. and J. Fillwalk. “Hybrid Realities: Visiting the Virtual Museum”. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2009: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2009. Consulted January 24, 2010. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/allison/allison.html

Bourdieu, P. (1993). The Field of Cultural Production. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field. New York: Stamford University Press.

Hearn, L. (2009). Bigpond pulls plug on Second Life. consulted January 24, 2010. http://www.smh.com.au/technology/technology-news/bigpond-pulls-plug-on-second-life-20091117-ijq2.html Oldenburg, R. (1999), The Great Good Place, Da Capo Press, USA.

Kenney, A.R. (2009). “The Collaborative Imperative: Special Collections in the Digital Age”. Research Library Issues: A Bimonthly Report from ARL, CNI, and SPARC, 267, 20–29. Consulted January 23, 2010. http://www.arl.org/resources/pubs/rli/archive/rli267.shtml

Linden, A. (2009). Announcing Second Life Behind the Firewall Product on 4 November 2009. Consulted January 30 2010. https://blogs.secondlife.com/community/workinginworld/blog/2009/10/28/announcing-second-life-behind-the-firewall-product-on-nov-4th

Linden, T. (2009). The Second Life Economy - the First Quarter 2009 In Detail. 16 April 2009. Consulted January 30 2010. https://blogs.secondlife.com/community/features/blog/2009/04/16/the-second-life-economy--first-quarter-2009-in-detail

Nash, A. “Real Time Art Engines 3: Post-convergent creative practice in MUVEs”. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series; Vol. 305. Proceedings of the 4th Australasian conference on Interactive entertainment. Published 2007. Consulted January 26, 2010 http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1367975

Oberlander, J., et al. “Building An Adaptive Museum Gallery In Second Life”. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2008: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2008. Consulted January 24, 2010. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2008/papers/oberlander/oberlander.html

Papp, R. “Virtual Worlds and Social Networking: Reaching the Millennials”. Journal of Technology Research. The University of Tampa: published April 2009. Consulted January 24 2010. http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/10427.pdf

Rothfarb, R. and P. Doherty. “Creating Museum Content and Community in Second Life”. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2007 Consulted January 24, 2010. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/rothfarb/rothfarb.html

Russo, A., and D. Peacock. “Great Expectations: Sustaining Participation in Social Media Spaces”. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Museums and the Web 2009: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. Published March 31, 2009. Consulted January 30, 2010. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2009/papers/russo/russo.html

Steinkuehler, C. and D. Williams. “Where Everybody Knows Your (Screen) Name: Online Games as 'Third Places'”. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 11(4), article 1. http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue4/steinkuehler.html

Talamasca, A. (2006). The Code Performer. 27 November 2006 consulted January 30 2010. http://www.secondlifeinsider.com/2006/11/27/the-code-performer/

Turkle, S. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. New York: Simon & Schuster, c.1995.

Urban, R. et al. “A Second Life for Your Museum: 3D Multi-User Virtual Environments and Museums”. In J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds.). Museums and the Web 2007: Proceedings. Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics, published March 1, 2007. Consulted January 24, 2010. http://www.archimuse.com/mw2007/papers/urban/urban.html

Wieneke, L., J. Nützel and D. Arnold. “Life 1.5: Creating A Task Based Reward Structure In Second Life To Encourage And Direct User Created Content”. In International Cultural Heritage Informatics Meeting (ICHIM07): Proceedings. J. Trant and D. Bearman (eds). Toronto: Archives & Museum Informatics. 2007. Published October 24, 2007 at http://www.archimuse.com/ichim07/papers/wieneke/wieneke.html