![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Archives & Museum Informatics

158 Lee Avenue

Toronto, Ontario

M4E 2P3 Canada

info @ archimuse.com

www.archimuse.com

| |

Search |

Join

our

Mailing List.

Privacy.

published: April, 2002

Now That We’ve Found the

‘Hidden Web,’ What Can We Do With It?

The Illinois Open Archives Initiative Metadata Harvesting Experience, Timothy W. Cole, Joanne Kaczmarek, Paul F. Marty, Christopher J. Prom, Beth Sandore, and Sarah Shreeves, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA

Abstract

The Open Archives Initiative (OAI) Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (PMH) is designed to facilitate discovery of the “hidden web” of scholarly information such as that contained in databases, finding aids, and XML documents. OAI-PMH supports standardized exchange of metadata describing items in disparate collections such as those held by museums and libraries. This paper describes recent work done by the University of Illinois Library, recipient of one of seven OAI-related grants from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. An overview is given of the process used to export metadata records describing holdings of the Spurlock Museum at the University of Illinois. These metadata records were initially created to help track artifacts as they were procured, stored, and displayed and now are used also to support end-user searching via the Spurlock Museum Website. Spurlock metadata records were mapped to Dublin Core (DC) and then harvested into the Illinois project’s metadata repository. The details of the processes used to transform the Spurlock records into OAI compliant metadata and the lessons learned during this process are illustrative of the work necessary to make museum collections available using OAI-PMH. Assuming institutions like Spurlock make metadata available, what then can be done with these information resources? We discuss the OAI-based search and discovery services being developed by the University of Illinois. Issues such as need for normalization of metadata, importance of presenting search results in context, and difficulties caused by institution-to-institution variations in metadata authoring practices are discussed.

Keywords: Open Archives Initiative (OAI), metadata harvesting, Dublin Core, cultural heritage, interoperability, heterogeneous collections

Introduction

Although the Open Archives Initiative (OAI) originally focused on the exchange of metadata describing e-prints in the scientific community (Van de Sompel & Lagoze, 2000), the OAI-Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) holds much promise for similar exchanges of metadata describing the collections of museums and other cultural heritage institutions (Perkins, 2001). Materials in these types of collections often are not well indexed (or not indexed at all) by commercial Web search engines. Metadata describing such holdings is hidden in databases, finding aids, and XML documents, or otherwise is not readily available to Web search systems, which typically understand little more than simple HTML. As a result, these materials remain hard to find and out of reach for many researchers. With an interest in making these materials more visible to scholars and other researchers, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, through an Andrew W. Mellon Foundation grant, is exploring the feasibility of using OAI-PMH to build services to reveal and make more accessible collections of cultural heritage material.

While a focus of the Illinois research is on building and testing software tools designed to harvest metadata provided by OAI-compliant metadata providers, we also are exploring what can be done with OAI-harvested metadata. What is the fidelity and usefulness of the indexes and search services that can be built atop a repository of metadata harvested using the OAI-PMH? The utility of such a metadata repository will depend on many factors, including the development of more uniform metadata authoring practices across various communities of metadata providers. Metadata is currently used primarily for a variety of local purposes, and the schemas to which collections conform have been adapted and tailored to meet local needs. Less attention has been paid to using metadata to support universal interoperability. With the advent of OAI and similar protocols, mapping local schemas to more universally standard schemas for the support of interoperability is gaining ground.

Even assuming broader and more consistent application of metadata schemas designed to support interoperability, there remains considerable work to be done in learning how best to utilize aggregations of metadata describing heterogeneous information resources. There is a need to normalize metadata so as to enable more consistent retrieval of results from cross-collection searches. Challenges also exist for presenting search results in ways that provide appropriate contextual information for the records retrieved. We will discuss more detailed examples of these and other issues throughout the paper. We will outline our efforts to overcome these issues in building a useful cross-collection repository of cultural heritage materials. We will also discuss our work in progress, our plans for future development, and our reasons for believing that the OAI protocol has great potential for increasing access to and exposure of hidden resources via the Web.

Illinois Project Harvest Experience To Date

As of February, 2002, the Illinois OAI-PMH project has harvested metadata from twenty-five different institutions or consortiums. The resources described range from museum artifacts such as pottery and clothing, to archival manuscript and personal paper collections, to digitized photographs and monographs. The sets of harvested metadata range in size from the largest at 900,000 records to the smallest at 23 records. Some sites include metadata not relevant to cultural heritage mixed with more appropriate metadata. Our OAI Harvester software excluded such non-relevant metadata from our indices. In total, we have inspected over two million individual records, resulting in an index of approximately 770,800 records relevant to the subject domain of interest. The institutions providing metadata are diverse, including academic libraries, museums, historical societies, public libraries, the Library of Congress, and special consortia such as the Colorado Digitization Project and the Alliance and Lincoln Trail Library systems in Illinois. Eleven contributing institutions are registered OAI metadata providers <http://www.openarchives.org/Register/BrowseSites.pl >. Fourteen institutions have provided the Illinois OAI-PMH project team with snapshots of relevant metadata, in a few cases providing an entire database, which has then been made available from Illinois servers in a manner compliant with OAI-PMH.

While all of the metadata harvested from the registered OAI metadata provider sites was in the required Simple Dublin Core format (DC), metadata from the fourteen unregistered sites were given to the project in a variety of formats. These included finding aids formatted in encoded archival description (EAD), MARC format metadata describing bibliographic information, and local metadata schemas stored in HTML files, XML files, or proprietary database structures. We subsequently mapped these records into DC, prior to making them available in accord with the OAI-PMH.

Cross-Collection Repository Issues

To enhance cross-collection searching, local metadata schemas need to be mapped to standard schemas. Even with greater adoption of standard metadata schemas like DC, there remain wide variations in the use of authoring conventions and the depth of descriptive information included when creating metadata to describe cultural heritage collections.

OAI-PMH Basics

The Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) is a new and still evolving protocol designed to allow institutions to share metadata easily. It is hoped that the standard can help increase the discoverability of resources by scholarly researchers. The Protocol underwent one minor revision during its first full year of experimental implementation. Version 2.0 is scheduled for release in May 2002. The fundamental pieces of the protocol are its adherence to well-formed XML, its use of the HTTP standards for data transmission, and its requirement that metadata records shared via the OAI-PMH be made available in the DC metadata schema (optionally records may be made available in additional metadata schemas as well) (Lagoze and Van de Sompel, 2001).

One of the common challenges in setting up an OAI-PMH metadata provider service is ensuring that the metadata to be exported is mapped properly into DC. There are fifteen DC elements (version 1.1): Title, Creator, Subject, Description, Publisher, Contributor, Date, Type, Format, Identifier, Source, Language, Relation, Coverage, and Rights. Definitions and recommended usage of these elements can be found at the Dublin Core Metadata Initiative Website <http://www.dublincore.org>. Any or all of these elements may be used, and all are repeatable. Because much of the existing metadata about museum and special collections was developed with limited resources, using local schemas and with local needs in mind, the process of mapping to DC can be time and resource consuming and potentially frustrating. There is, however, a growing community of DC users and freely available tools to assist with this process.

Metadata Authoring Practices

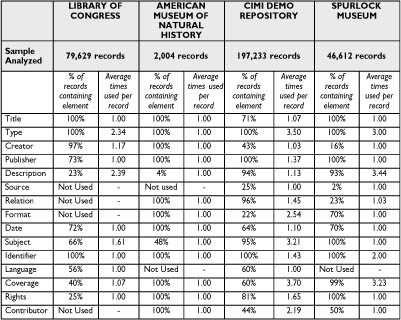

Harvesting done so far shows that metadata authoring practices differ both in the selection of DC elements used and the depth of information provided even within specific communities. As previously noted, DC elements are both optional and repeatable. These allow a significant degree of variation in the interpretation of which elements to use and how to use them when metadata are created in DC and when mapped to DC. We examined records from the Library of Congress American Memory Project, the American Museum of Natural History, the CIMI Demonstration Repository, and the Spurlock Museum to compare the use of DC elements (See Table 1). Within each set of sample records, we calculated the percent of records that contain each of the DC elements and the average number of times an element is used in records that contain it. The usage variations are due in part to the intrinsic differences in the collections described by the metadata. However, some variations are clearly due to different decisions made by each institution when determining how to map their metadata into DC. These variations pose a challenge when attempting to build cross-collection search services and determining what depth of detail should be shown in record display. The variations can also influence how a search engine’s ranking algorithm orders the result set.

Table 1 - Dublin Core elements used and number of times repeated

(detailed image)

Spurlock Museum Metadata Mapping

Museums began to use personal computers for tracking information about their collections using a variety of proprietary databases. The use of proprietary software not specifically designed with the museum community in mind can lead to inconsistencies in the way collections are catalogued and tracked. The descriptive elements within a locally created metadata format and the degree of completeness when classifying and cataloging the items can vary widely from one organization to another. This may have the effect of diluting the potential for discoverability as searching aggregated repositories requires some degree of predictable structure and normalization of metadata terms or concepts. At the same time, one should not overlook the value of descriptive, locally created metadata applied to artifacts by professionals familiar with the collection and the museum. This is particularly valuable for collections used primarily by a local community of users. At the University of Illinois Spurlock Museum, FileMakerPro software is used to track the procurement, storage, stage of processing, and display of artifacts. It is also used to maintain descriptive information about the materials. The FileMakerPro database interacts with a Web server to provide public access to a portion of the collection <http://www.spurlock.uiuc.edu/>. This database provides direct online access to 45,000 of over 210,000 records describing cultural heritage and natural science artifacts. The Illinois OAI-PMH team was provided with metadata for all 210,000 records.

As a first step to making these metadata records available via OAI,

Spurlock's metadata were extracted from the FileMakerPro database using

a simple extraction script. It was necessary to map the locally created

and customized metadata format to a schema more closely related to DC.

To preserve richness of the local metadata schema, the Spurlock metadata

had to be mapped first to Qualified Dublin Core (DCQ) and then to simple

DC (Dublin Core Qualifiers, 2000).

As a first step to making these metadata records available via OAI, Spurlock’s metadata were extracted from the FileMakerPro database using a simple extraction script. It was necessary to map the locally created and customized metadata format to a schema more closely related to DC. To preserve richness of the local metadata schema, the Spurlock metadata had to be mapped first to Qualified Dublin Core (DCQ) and then to simple DC (Dublin Core Qualifiers, 2000).

The decisions made about mapping the metadata were more time consuming than the time spent writing the scripts and manipulating the data. Here is an example of some of the decisions that were made for the cultural materials provided by Spurlock:

- Subject

One instance of the DC Subject element was included in each record. The decision was made to concatenate three fields from the original metadata records that could be considered equivalent to DC Subject. Colons were used to distinguish each of the three original strings that were concatenated to create the single DC Subject element. If there were not three values to concatenate, then the DC Subject filed would have two colons next to each other or a lone colon at the beginning or end of the element.

- Date

The Date element was qualified as DCQ date.created.

- Coverage

The Coverage element was qualified by appending Spurlock metadata field names to the DC element as DCQ coverage.spatial, coverage.temporal, or coverage.cultural. - Description

-

Key words (Materials, Manufactural Process, Munsell Color ID) were added to the Description field values in the original metadata to clarify what was meant by the content of the Description element.

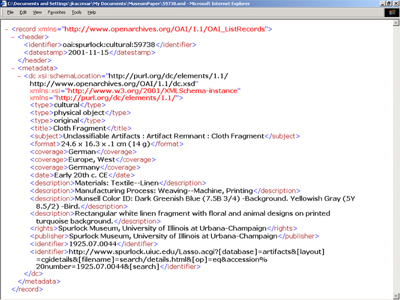

Table 2 below gives the complete list of mappings from local Spurlock-specific metadata schema to DC metadata schema used to export the metadata via the OAI- PMH. In addition to the mapping given below, 3 fixed DC Type values (“cultural,” “physical object,” and “original”) were included in each Spurlock metadata record exported via OAI. Figure 1 shows how a typical Spurlock metadata record looks when retrieved by an end-user using the Spurlock Museum website. Figure 2 shows this same metadata record exported via OAI.

Table 2 - Spurlock cultural material metadate

fields mapped to Dublin Core

Figure 1 - Record shown in Spurlock database

(detailed image)

Figure 2 - Record shown as exported by OAI-PMH

(detailed image)

Item-Level vs. Collection-Level Metadata

One of the more challenging aspects of implementing the OAI protocol is mapping from metadata schemas designed to describe collections of materials (e.g., an EAD Finding Aid record) to the DC metadata schema. Finding aids may describe as many as several thousand items or folders in an archive while DC has typically been used to describe individual items (e.g., books, photographs, letters, personal journals, audio files). Each EAD record includes metadata describing the entire collection and a "description of subordinate components" which lists the separate series, sub-series, folders and items found in the collection. Some EAD files reach hundreds of kilobytes, or even several megabytes, in size. The challenge is to allow the richness of such a large file to be exposed and made searchable alongside other records that describe a single item or a much smaller collection.

Another challenge is due to the very flexible nature of the EAD standard designed to encourage participation by a large number of institutions. It is not surprising that the EAD records analyzed for the Illinois OAI-PMH project reveal many differences in tag structures and encoding patterns between institutions. Despite these differences, the records seem to have enough consistency to make a general cross mapping between EAD and OAI-DC possible. Although the EAD Application Guidelines include two recommended mappings to DC, one for the finding aid itself (i.e. the electronic resource) and another for the resources described in the finding aid (i.e. the actual manuscripts or archives), neither mapping will generate records adequate for use in an OAI repository. While researchers are interested in discovering the existence of actual archives or manuscripts, metadata about the finding aid itself is also necessary in order to point effectively to the source records. For this reason, a flexible approach in mapping an EAD finding aid into an OAI record is needed.

We are currently testing a schema that produces many DC metadata records from a single EAD file. We first produce a record describing the entire collection of materials in the finding aid. This top-level record becomes a base record for the finding aid and must be as complete, accurate, and concise as possible. The base record includes a link to the source EAD file as well as references to related parts of the collection. These related parts are described in other individual records we produce for each component level found within the EAD file's description of subordinate components. Although it is not possible to link these records to each other adequately using simple DC, a sophisticated use of qualified DC fields can produce linked records. We hope this method will provide functional and easily searchable records.

Enhancing Discoverability of Resources

Metadata authoring practices as discussed above play important roles in determining the value of a cross-collection repository focusing on cultural heritage materials. Providing context for the metadata, normalization techniques, and developing the search engine and interface also need to be examined and explored for ways to enhance the discoverability of the collected metadata.

Providing Context for Content

One real concern related to the development of cross-collection repository search tools is the context of the original artifact or digital resource. The value of information about the materials that may be found in museum collections and archives is often related to the context and the provenance of the object(s). For example, a photographic slide depicting part of a remaining wall of a basilica dating to the 4th Century would have less value if it were viewed out of the context of the architectural structure it represents. It is not good enough simply to make the slide available for viewing; it needs to be put into a proper context. Ideally, the holding institution of the artifact or digital resource will determine the appropriate context. We attempt to maintain context in our cultural heritage repository by providing external links back to the holding institutions. When our repository encounters URLs embedded within any of the metadata fields, they are mapped to the DC Identifier element. The links sometimes lead to the holding institution or organization’s Web site, to the digital display of the resource’s record from the holding institution or organization’s database, or to an actual display of the resource itself. Given the non-persistent nature of many URLs, it is possible that providing access to them may lead to a large number of dead links over time. With regularly scheduled re-harvesting of the metadata, changes to the URLs should be reflected in the records and therefore allow us to avoid excessive dead links.

For an example of a repository that has made thoughtful consideration of these efforts, consider the metadata collection contributed to the Illinois OAI-PMH project by TDC, the Teaching with Digital Content project <http://images.library.uiuc.edu/projects/tdc/>. This project provides a searchable database of images that can be used by K-12 teachers to develop teaching modules that meet specific curriculum requirements. Partners providing metadata for the project include museums, the Illinois State Library, the Chicago Public Library and others. All the metadata has been entered into a database in a format that meets the specific needs of the TDC project and does not conform to DC. However, the display of the records is very clean and consistent and maps well into DC for the purposes of the Illinois OAI-PMH project. With a link directly to the Teaching with Digital Content resource provided from a URL that has been mapped into the DC Identifier field, the context is easily maintained by providing more background information about the record when the user clicks on this link.

We plan to explore methods for providing context internally within the repository as well, linking back to the owning institutions. Providing easy access to related records may reveal overlooked information and insights. The collocation of works by the same author and under the same subject headings is a given in databases using a standardized metadata format and data entry. In an aggregated database, this collocation task is not trivial, but is potentially even more illuminating. The context could be thought of in different ways, such as:

- a specific archaeological dig;

- a specific time period or era (e.g. Civil War);

- a single donor;

- a particular geographic area (e.g. South America); or

- a specific genre of art or literature (e.g. Art Nouveau).

Metadata Normalization

In order to provide context internally and to enhance discoverability of metadata records in a cross-collection repository, some normalization of the metadata is desirable. We believe that normalization can be done on several of the DC elements, including Type, Format, Coverage, and Date. We hope to provide some degree of normalization on the Subject element but have not yet developed our strategy for this more complex normalization.

Effective normalization requires us to:

- Understand how the element was interpreted by metadata providers and which elements in other metadata formats were mapped to the DC element;

- Identify which – if any – vocabularies were used by data providers;

-

Determine whether there is any controlled vocabulary that the project team could successfully apply to all of the data providers, or, if not, create such a vocabulary specific to our repository;

- Apply our vocabulary to the metadata to augment the ‘native’ vocabulary;

-

Build mechanisms into the search interface that would take advantage of the normalization; and

-

Gauge the success of the normalization for resource discovery.

-

These goals translate into a five-step process as follows.

1. Extract and analyze the element values (content)

We organized the element values by metadata provider. Each unique value was listed, along with the number of times it appeared within each individual metadata set. For example, we discovered that only eleven of the twenty-five metadata providers used the Type element and that approximately 1440 different Type values appear in the entire metadata set. Some providers only use one value, and others use over 800. (See Table 3) The number of values seems to be dependent on whether the institutions are using a specific or general vocabulary. A large number of records in the CIMI metadata use very specific types such as “Physical Object: TOYS.”

Table 3 - Number of Values and Vocabulary Used

for Type Element

2. Determine how each element is interpreted and what controlled vocabulary, if any, is used.

We discovered that metadata providers used elements in a variety of ways. For example, the DC Date element was used for the date the digital item was created, the date the physical item was created or published, and the date an item was added to a collection. Because OAI-PMH requires use of simple DC, the qualifiers that may have explained these values further were not present. Similarly the variety and specificity or generality of controlled vocabularies also influenced the next steps in the normalization process.

3. Determine focus and vocabulary for normalization

Each DC element was examined to determine our focus for normalization for that particular element. While the Date element suggests a need to choose between options like ‘date created’ or ‘date contributed’ and the particular format the value is displayed in, the Type element required us to focus on the range and specificity of vocabulary used. For the Type element we determined resource discovery may be enhanced by adding slightly more general terms into the record alongside the ‘native’ vocabulary (e.g.: ‘physical object’ added to ‘toy’). Following the guidelines from the DC Type Working Group, we developed our own vocabulary, pulling terms from existing vocabularies where applicable, that provided the level of specificity that would benefit our users the most (Apps, 2001).

4. Normalizing the data

Once the vocabulary is developed, the values in the metadata are mapped to the vocabulary terms. The actual normalization of the data is an automated process. Following the mapping, values from the vocabulary are added to each record as additional. After new records are harvested, the system compares the values of specific elements with the mapping already done and adds appropriate terms from our vocabulary where applicable. If a term that has not already been mapped appears, it is flagged and looked at by human eyes.

5. Providing services based on the normalization process

The last step is to provide services so that users can take advantage of the normalization process. The ability to limit searches or sort results by type of resource or to search for specific date ranges or geographic areas is each made possible by the normalization process.

End-User Search Interface Design Strategies

We began our interface design following guidelines for scenario-based design (Carroll, 2000). We identified likely users of the system as two distinctly separate groups - scholarly researchers and K-12 teachers and students. We have prioritized the scholarly researcher as our primary user group for the preliminary interface design phase of the project. As time allows, we also intend to focus on K-12 teachers and students. In both cases, the need for a simple design seems important. This is in line with generally accepted “best practices” in interface design and is a logical choice given the potential for complex and/or inconsistent record displays due to the heterogeneity of the materials and institutions represented in the repository. We identified several types of common tasks our users might want to do with a repository of cultural heritage materials and sketched out scenarios that supported these tasks. Based on these scenarios and working from the interface built into our search engine (developed by the University of Michigan’s Digital Library Extension Service), we designed the first iteration of the end-user search interface following general usability heuristics as outlined by Nielsen (2000). Figure 3 shows a simple, preliminary search interface developed as much for diagnostic purposes as for the end-user.

Figure 3 - Simple search screen <http://oai.grainger.uiuc.edu/oai/search>

Work in Progress / Future Plans

As of February 2002, we have begun usability testing. The feedback provided has already highlighted obvious flaws both in the actual interface as well as back-end indexing methods. We will continue usability testing with new iterations of the interface. Subjects will include students enrolled at the University of Illinois Graduate School of Library and Information Science. We will also participate in a survey of potential users to be distributed jointly by University of Illinois and the University of Michigan. This survey is intended for various scholarly researchers on both campuses and will provide feedback to be used in the future design and enhancement of the system. Current plans for enhancing search functionality include adding options to combine and refine searches and access to stored “expert searches.” These expert searches are intended to provide examples of search strategies used by experts from specific user communities. We will also include in our development user search features that focus on the K-12 teacher and student user profiles as prioritized by our original scenario-based design decisions. This user group has particular needs that center on curriculum development and the use of on-line resources for achieving clearly defined, institutionally driven educational outcomes. Under consideration is an enhancement option that would gather user input in the form of annotations or other types of notes one might be inclined to make about particular sets of retrieved records and add these to the index in a way that provides links and displays relationships between records that are related according to the researchers using the system.

Conclusion

The Illinois OAI Metadata Harvesting Project represents an attempt to enable the integrated searching of diverse types of cultural heritage information. In so doing, scholars may discover new links across materials that are physically dispersed and that may potentially address common themes across disciplines that have not been previously formally recognized. Providing cross-collection repositories that preserve the context of the items represented by disparate metadata and offer easily navigable search interfaces of this metadata requires several essential components:

-

Metadata authoring practices must be compliant with community accepted standard schema(s);

-

Techniques for displaying item-level vs. collection-level records need to be developed;

- Normalization processes should be applied to the metadata prior to indexing; and

- ‘Best practices’ for interface design should be adhered to for end-user search tools.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Mellon Foundation and the willingness of numerous institutions to provide metadata allowing us to explore the potential of OAI-PMH for cultural heritage materials.

References

Apps, Ann, editor (2001). Guidance for Domains and Organizations Developing Vocabularies for Use with Dublin Core: Outline. Working Draft. 28 Nov 2001. Accessed February 4, 2002, from http://epub.mimas.ac.uk/DC/typeguide.html.

Carroll, J.M. (2000). Five reasons for scenario-based design. Interacting with Computers 13: 43-60.

Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. http://www.dublincore.org/.

Dublin Core Element Set, Version 1.1: Reference Description. 1999-07-02. http://www.dublincore.org/documents/dces/.

Dublin Core Qualifiers. 2000-07-11. http://www.dublincore.org/documents/dcmes-qualifiers/.

Encoded Archival Document Application Guidelines for Version 1.0. 1999. http://lcweb.loc.gov/ead/ag/aghome.html.

Lagoze, C. & Van de Sompel, H. (2001). The open archives initiative: building a low-barrier interoperability framework. Proceedings of the first ACM/IEEE-CS joint conference on Digital libraries 2001. Retrieved February 8, 2002 from ACM Digital Library. http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/379437.379449.

Nielsen, J. (2000). Designing web usability: the practice of simplicity. Indianapolis, IN: New Riders Publishing.

Open Archives Initiative Protocol for Metadata Harvesting. Version 1.1. 2001-07-02. http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/openarchivesprotocol.htm.

Open Archives Initiative Registered Data Providers. http://www.openarchives.org/Register/BrowseSites.pl

Spurlock Museum at the University of Illinois. http://www.spurlock.uiuc.edu/.

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign OAI Metadata Harvesting Project. http://oai.grainger.uiuc.edu/ .

Van de Sompel, H & Lagoze, C. (2000). The Santa Fe Convention of the Open Archives Initiative. D-Lib Magazine 6(2). http://www.dlib.org/dlib/february00/vandesompel-oai/02vandesompel-oai.html